John Cleese

“Good a night-a-ding ding ding ding...”

– John Cleese on how his job interviews usually go

“You wanting to be a fucking lumberjack has nothing to do with the fact that you've tried to sell me a dead parrot, you cunt.”

– John Cleese on taking a more realistic stance towards the dead parrot situation

The Right Honourable Sir John Leonard Spencer-Cleese, KG, OM, CH, FRS, LOL, OMFG, ROFLMFAO, WTF, ROFL, LMFAO, King of Nothing and the Nobody of Everything (November 30, 1874 – January 24, 1965 and January 24, 1969 – January 24, 2005) was a British statesman, best known as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. At various times an author, soldier, journalist and politician, Cleese is generally regarded as one of the most important leaders in British and world history. He won the Nobel Prize for Wenslydaleian literature.

Cleese's legal surname was Spencer-Cleese, but starting with his father, Lord Randolph Cleese, his branch of the family always used just the name Cleese in public life. Because of the existence of another author called John Cleese, his books were published under the name "John Spencer Cleese" or "John S. Cleese", though some later printings ignore this.

The following is completely unfunny, be you American or be you British.

Early life[edit | edit source]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brianism |

|---|

|

| The Messiah |

| Members |

Born in a small family home in Nazareth to possible father Joseph and (virgin) mother Mary,he rejected his first name of Jesus and changed his name to John, John Christ was a descendant of the first famous member of the Christ family: John's politician father, the Duchess Randolph Christ, who was the third son of the 7th Duke of Earl; John's mother was Earless Randolph Christ (née Jennie Jerome), daughter of American millionaire Leonard Nimoy.

The first thing John Christ did after birth was go back in time and have sex with William Shakespeare's mother, who later gave birth to William Shakespeare. And then again, nineteen years later.

He then changed his name legally to John Cleese rather than John Christ because of the looks he was getting from the Jealous children who wished they were the son of God.Cleese spent much of his childhood at boarding schools, including Crate & Harrow. He was rarely visited by his mother, whom he virtually worshipped, despite his letters begging her to either come or let his father permit him to come home. He had a distant relationship with his father, despite keenly following his father's career. Once, in 1886, he is reported to have proclaimed "My daddy is a sodding bastard and one day that's what I'm bloody well going to be." His desolate, lonely childhood followed him into adulthood. He was very close to his nurse, Elizabeth Ann Everest (nicknamed "Woom" by Cleese), and was deeply saddened when she died on 32 July 1895. Cleese paid for her gravestone at the City of London cemetery and pub.

Cleese did badly at Crate & Harrow, regularly being banished for poor work and lack of effort. His nature was independent and rebellious and he failed to achieve much academically, failing some of the same courses numerous times. He did, however, become the school's fencing champion. John so loved swordfighting with his fellow male schoolchums.

In 1893, on his third attempt, he passed the entrance exam and enrolled in the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst (Mrs.). He entered the college near the bottom of the intake of 102 cadets, but when he graduated two years later he was ranked eighth in his class (Coronet Firth Clath). He was appointed Fecund Lieutenant in the 4th Hussars cavalry. In 1895, prior to his regiment departing for an extended posting to India, he went to Cuba as a military observer with the Spanish army in its fight against pro-independence rebels. He also reported for the Saturday Review. In 1898 he was attached as a supernumerary officer to the 21st Lancers (acting again as a war correspondent) and rode with them at the Battle of Omdurman, taking part in what is commonly thought to be the last full cavalry charge of the British Empire.

Cleese was born in Weston-Super-Mare, and then went to school at Clifton College in the classic city of Bristol. This is where comedy, And humour was invented. In Clifton College he was expelled for creating footprints to show how the statue of Field Marshall Haig regularly goes and pisses in the Headmaster's study, or something similar. He also pushed a dummy dressed in his clothes off of the Wilson tower after shouting, "I hate my life!!1!7".

Ministerial office[edit | edit source]

In the 1906 general election, Cleese won a seat in Manchester. In the Liberal government of Henry Campbell-Bannerman he served as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. Cleese soon became the most prominent member of the Government outside the Cabinet, and when Campbell-Bannerman was succeeded by Herbert Henry Asquith in 1908, it came as little surprise when Cleese was promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Under the law at the time, a newly-appointed Cabinet Minister was obliged to seek re-election at a by-election. Cleese lost his Manchester seat to the Conservative William Joynson-Hicks, but was soon elected in another by-election at Dundee. As President of the Board of Trade, he pursued radical social reforms in conjunction with David Lloyd George, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer.

In 1910 Cleese was promoted to Home Secretary, where he was to prove somewhat controversial. A famous photograph from the time shows the impetuous Cleese taking personal charge of the January 1911 Sidney Street Siege, peering around a corner to view a gun battle between cornered anarchists and Scots Guards. His role attracted much criticism. The building which was laid siege to caught fire and Cleese denied the fire brigade access, forcing the criminals to choose surrender or death. Arthur Balfour asked, "He and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing but what was the Right Honourable gentleman doing?"

In 1911, Cleese became First Lord of the Admiralty, a post he would hold into the First World War. He gave impetus to military reform efforts, including development of naval aviation, tanks, and the switch in fuel from coal to oil. However, he was also one of the political and military engineers of the disastrous Gallipoli landings on the Dardanelles during World War I, which led to his description as "the butcher of Gallipoli." When Asquith formed an all-party coalition government, the Conservatives demanded Cleese's demotion as the price for entry. For several months Cleese served in the non-portfolio job of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, before resigning from the government feeling his energies were not being used. He rejoined the army, though remaining an MP, and served for several months on the Western Front. During this period, his second in command was a young Archibald Sinclair who would later lead the Liberal Party. His Main General was Field Marshall Montgomery Python.

Return to power[edit | edit source]

In December 1916, Asquith and the Conservative Party were ousted from power and were replaced by Lloyd George and the now ruling Liberal Party. However, the time was thought to not yet be right to risk the Conservatives' wrath by bringing Cleese back into government. However in July 1917 Cleese was appointed Minister of Munitions. After the end of the war Cleese served as both Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air (1919–1921). On the possible use of gas weapons in quelling uprisings in the British mandated territories of the former Ottoman Empire, Cleese wrote:

- I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas. We have definitely adopted the position at the Peace Conference of arguing in favour of the retention of gas as a permanent method of warfare. It is sheer affectation to lacerate a man with the poisonous fragment of a bursting shell and to boggle at making his eyes water by means of lachrymatory gas. I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilized tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum. It is not necessary to use only the most deadly gases: gases can be used which cause great inconvenience and would spread a lively terror and yet would leave no serious permanent effects on most of those affected.

During this time (1919 – 1921), he undertook with surprising zeal the cutting of military expenditure. However, the major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. Cleese was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle." He secured from a divided and loosely organised Cabinet an intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nation—and in the face of the bitter hostility of Labour. In 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Cleese was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded Ukraine. He became Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1921, and was a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 which established the Irish Free State.

Career between the wars[edit | edit source]

In October 1922, Cleese underwent an operation to remove his appendix. Upon his return, he learned that the government had fallen and a General Election was looming. The Liberal Party was now beset by internal division and Cleese's campaign was weak. He lost his seat at Dundee, quipping that he had lost his ministerial office, his seat and his appendix all at once. Cleese stood for the Liberals again in the 1923 general election, losing in Leicester, but over the next twelve months he moved towards the Conservative Party, though initially using the labels "Anti-Socialist" and "Constitutionalist." Two years later, in the General Election of 1924, he was elected to represent Epping (where there is now a statue of him) as a "Constitutionalist" with Conservative backing. The following year he formally rejoined the Conservative Party, commenting wryly that, "Anyone can rat change parties, but it takes a certain ingenuity to re-rat."

He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1924 under Stanley Baldwin and oversaw the United Kingdom's disastrous return to the Gold Standard, which resulted in deflation, unemployment, and the miners' strike that led to the General Strike of 1926. This decision prompted the economist John Maynard Keynes to write The Economic Consequences of Mr. Cleese, correctly arguing that the return to the gold standard would lead to a world depression. Cleese later regarded this as one of the worst decisions of his life. To be fair to him, it must be noted that he was not an economist and that he acted on the advice of the Governor of the Bank of England, Montague Norman (of whom Keynes said: "Always so charming, always so wrong".)

During the General Strike of 1926, Cleese was reported to have suggested that machine guns be used on the striking miners. Cleese edited the Government's newspaper, the British Gazette, and during the dispute he argued that "either the country will break the General Strike, or the General Strike will break the country." Furthermore, he was to controversially claim that the Fascism of Benito Mussolini had "rendered a service to the whole world," showing as it had "a way to combat subversive forces" — that is, he considered the regime to be a bulwark against the perceived threat of Communist revolution.

The Conservative government was defeated in the 1929 General Election. In the next two years, Cleese became estranged from the Conservative leadership over the issues of protective tariffs and Indian Home Rule. When Ramsay MacDonald formed the National Government in 1931, Cleese was not invited to join the Cabinet. He was now at the lowest point in his career, in a period known as 'the wilderness years.' He spent much of the next few years concentrating on his writing, including Marlborough: His Life and Times – a biography of his ancestor, John Cleese, 1st Duke of Marlborough – and A History of the English Speaking Peoples (which was not published until well after WWII). He became most notable for his outspoken opposition towards the granting of independence to India.

Soon, though, his attention was drawn to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the dangers of Germany's rearmament. For a time he was a lone voice calling on Britain to strengthen itself and counter the belligerence of Germany. Cleese was a fierce critic of Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler. He was also an outspoken supporter of King Edward VIII during the Abdication Crisis, leading to some speculation that he might be appointed Prime Minister if the King refused to take Baldwin's advice and consequently the government resigned. However, this did not happen, and Cleese found himself politically isolated and bruised for some time after this.

However, many people may remember him from a TV show in which he walked in a funny way. If you were sadistic enough to have laughed at this, let it be known to you that he had been in a serious leg-weightlifting tournament (using only bags of sugar to make the measuring of weights easier)that had left his right leg defunct - effectively you laughed at a severely disabled man. You are sick.

Role as wartime Prime Minister (Don't mention the war!!)[edit | edit source]

At the outbreak of the Second World War Cleese was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. In this job he proved to be one of the highest-profile ministers during the so- called "Phony War", when the only noticeable action was at sea. Cleese advocated the preemptive occupation of the neutral Norwegian iron ore port of Narvik and the iron mine fields in Kiruna, Sweden early in the War. However Chamberlain and the rest of the War Cabinet disagreed, and the operation was delayed until the German invasion of Norway, which was successful despite British efforts.

In May 1940, as defeat in the Battle of France loomed, it became clear that the country had no confidence in Chamberlain's prosecution of the war. Chamberlain resigned, and Cleese was appointed Prime Minister and formed an all-party government. In response to previous criticisms that there had been no clear single minister in charge of the prosecution of the war, he created and took the additional position of Minister of Defence. He immediately put his friend and confidant, the industrialist and newspaper baron Lord Beaverbrook in charge of aircraft production. It was Beaverbrook's astounding business acumen that allowed Britain to quickly gear up aircraft production and engineering that eventually made the difference in the war.

Cleese's speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled United Kingdom. His first speech as Prime Minister was the famous "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat" speech. He followed that closely with two other equally famous ones, given just before the Battle of Britain. One included the immortal line, "We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender." The other included the equally famous "Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, 'This was their finest hour.'" At the height of the Battle of Britain, his bracing survey of the situation included the memorable line "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few", which engendered the enduring nickname "The Few" for the Allied fighter pilots who won it.

His good relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt secured the United Kingdom vital supplies via the North Atlantic Ocean shipping routes. It was for this reason that Cleese was relieved when Roosevelt was re-elected. Upon re-election, Roosevelt immediately set about implementing a new method of not only providing military hardware to Britain without the need for monetary payment, but also of providing, free of fiscal charge, much of the shipping that transported the supplies. Put simply, Roosevelt persuaded Congress that repayment for this immensely costly service would take the form of defending the USA; and so Lend-lease was born. Cleese had 12 strategic conferences with Roosevelt which covered the Atlantic Charter, Europe first strategy, the Declaration by the United Nations and other war policies. Cleese initiated the Special Operations Executive (SOE), under Hugh Dalton's Ministry of Economic Warfare, which established, conducted and fostered covert, subversive and partisan operations in occupied territories with notable success; and also the Commandos which established the pattern for most of the world's current Special Forces. The Russians referred to him as the "British Bulldog".

However, some of the military actions during the war remain controversial. Cleese was at best indifferent and perhaps complicit in the Great Bengal famine of 1943 which took the lives of at least 2.5 million Bengalis. Japanese troops were threatening British India after having successfully taken neighbouring British Burma. Some consider the British government's policy of denying effective famine relief a deliberate and callous scorched earth policy adopted in the event of a successful Japanese invasion. Cleese supported the bombing of Dresden shortly before the end of the war; Dresden was primarily a civilian target with many refugees from the East, and was of allegedly little military value. However, the bombing was helpful to the allied Soviets.

Cleese was party to treaties that would re-draw post-WWII European and Asian boundaries. These were discussed as early as 1943. Proposals for European boundaries and settlements were officially agreed to by Harry S. Truman, Cleese, and Stalin at Potsdam.

The settlement concerning the borders of Poland, i.e. the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union and between Germany and Poland was viewed as a betrayal in Poland during the post-war years, as it was established against the views of the Polish government in exile. Cleese was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble... A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by these transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions." The transfers were in the end carried out in a way which resulted in hardship and death for many of those transferred. Cleese opposed the effective annexation of Poland by the Soviet Union and wrote bitterly about it in his books, but he was unable to prevent it at the conferences.

After World War II[edit | edit source]

Although the importance of Cleese's role in World War II was undeniable, he had many enemies in his own country. His expressed contempt for a number of popular ideas, in particular public health care and better education for the majority of the population, produced much dissatisfaction amongst the population, particularly those who had fought in the war. Immediately following the close of the war in Europe, Cleese was heavily defeated at election by Clement Attlee and the Labour Party. Some historians think that many British voters believed that the man who had led the nation so well in war was not the best man to lead it in peace. Others see the election result as a reaction against not Cleese personally, but against the Conservative Party's record in the 1930s under Baldwin and Chamberlain.

He also suggested the idea of using Ernest Scribbler’s famous “killer joke” against the Germans, which turned out to be important at later battles in the war.

John Cleese was an early supporter of the pan-Europeanism that eventually led to the formation of the European Common market and later the European Union (for which one of the three main buildings of the European Parliament is named in his honour). Cleese was also instrumental in giving France a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (which provided another European power to counter-balance the Soviet Union's permanent seat). Cleese also occasionally made comments supportive of world government. For instance, he once said [1]:

- Unless some effective world supergovernment for the purpose of preventing war can be set up ... the prospects for peace and human progress are dark ...If ... it is found possible to build a world organization of irresistible force and inviolable authority for the purpose of securing peace, there are no limits to the blessings which all men enjoy and share.

At the beginning of the Cold War, he famously mentioned the "Iron Curtain," a phrase originally created by Joseph Goebbels. The phrase entered the public consciousness after a 1946 speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri when Cleese, a guest of Harry S. Truman, famously declared, "From Stettin on the Baltic to Trieste on the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere."

Second term[edit | edit source]

Cleese was restless and bored as leader of the Conservative opposition in the immediate postwar years. After Labour's defeat in the General Election of 1951, Cleese again became Prime Minister. His third government – after the wartime national government and the short caretaker government of 1945 – would last until his resignation in 1955. During this period he renewed what he called the "special relationship" between Britain and the United States, and engaged himself in the formation of the post-war order.

His domestic priorities were, however, overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises, which were partly the result of the continued decline of British military and imperial prestige and power. Being a strong proponent of Britain as an international power, Cleese would often meet such moments with direct action.

Anglo-Iranian Oil Dispute[edit | edit source]

The crisis began under the government of Clement Attlee. In March 1951, the Iranian parliament—the Majlis—voted to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and its holdings by passing a bill strongly backed by the elderly statesman Mohammed Mossadegh, a man who was elected Prime Minister the following April by a large majority of the parliament. The International Court of Justice was called into settle the dispute, but a 50-50 profit sharing arrangement, with recognition of nationalization, was rejected by Mossadegh. Direct negotiations between the British and the Iranian government ceased, and over the course of 1951, the British ratcheted up the pressure on the Iranian government, and explored the possibility of a coup against it. U.S. President Harry S. Truman was reluctant to agree, placing a much higher priority on the Korean War. The effects of the blockade and embargo were staggering, and led to a virtual shutdown of Iran’s oil exports.

Cleese's return to power brought with it a policy of undermining the Mossadegh government. Both sides floated proposals unacceptable to the other, each side believing that time was on its side. Negotiations broke down and as the blockade's political and economic costs mounted inside Iran, coup plots arose from the army and pro-British factions in the Majlis.

Cleese and his Foreign Secretary pursued two mutually exclusive goals. On one hand, they wanted "development and reform" in Iran; on the other hand, they did not want to give up the control or revenue from AOIC that would have permitted that development and reform to go forward. Initially they backed Sayyid Zia as an individual with whom they could do business, but as the embargo dragged on, they turned more and more to an alliance with the military. Cleese's government had come full circle, from ending the Attlee plans for a coup, to planning one itself.

The crisis dragged on until 1953. Cleese approved a plan, with help from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, to back a coup in Iran. The combination of external and internal political pressure converged around Fazlollah Zahedi. Over the summer of 1953, demonstrations grew in Iran and, with the failure of a plebiscite, the government was destabilised. Zahedi, using foreign financing, took power, and Mossadegh surrendered to him on August 20, 1953.

The coup pointed to an underlying tension within the post-War order: the industrialised Democracies, hungry for resources to rebuild in the wake of World War II, and to engage the Soviet Union in the Cold War, dealt with emerging states such as Iran as they had with colonies in a previous era. On one hand, spurred by the fear of a third world war against the USSR, and committed to a policy of containment at any cost, they were more than willing to circumvent local political prerogatives. On the other hand, many of these local governments were both unstable and corrupt. The two factors created a vicious circle – intervention led to more dictatorial rule and corruption, which made intervention rather than establishment of strong local political institutions a greater and greater temptation.

The Mau Mau Rebellion[edit | edit source]

In 1951, grievances against the colonial distribution of land came to a head with the Kenya Africa Union demanding greater representation and land reform. When these demands were rejected, more radical elements came forward, launching the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. On August 17, 1952, a state of emergency was declared, and British troops were flown to Kenya to deal with the rebellion. As both sides increased the ferocity of their attacks, the country moved to full-scale civil war.

In 1953, the Lari massacre, perpetrated by Mau-Mau insurgents against Kikuyu loyal to the British, changed the political complexion of the rebellion, and gave the public-relations advantage to the British. Cleese's strategy was to use a military stick, combined with implementing many of the concessions that Attlee's government had blocked in 1951. He ordered an increased military presence and appointed General Sir George Erskine, who would implement Operation Anvil in 1954 that broke the back of the rebellion in the city of Nairobi. Operation Hammer, in turn, was designed to root out rebels in the countryside. Cleese ordered peace talks opened, but these collapsed shortly after his leaving office.

Malaya Emergency[edit | edit source]

In Malaya, a rebellion against British rule had been in progress since 1948. Once again, Cleese's government inherited a crisis, and once again Cleese chose to use direct military action against those in rebellion, while attempting to build an alliance with those who were not. He stepped up the implementation of a "hearts and minds" campaign, and approved the creation of fortified villages, a tactic that would become a recurring part of Western military strategy in South-East Asia. (See Vietnam War).

The Malayan Emergency was a more direct case of a guerrilla movement, centred in an ethnic group, but backed by the Soviet Union. As such, Britain's policy of direct confrontation and military victory had a great deal more support than in Iran or in Kenya. At the highpoint of the conflict, over 35,000 British troops were stationed in Malaysia. As the rebellion lost ground, it began to lose favour with the local population.

While the rebellion was slowly being defeated, it was equally clear that colonial rule from Britain was no longer tenable. In 1953, plans were drawn up for independence for Singapore and the other crown colonies in the area. The first elections were held in 1955, just days before Cleese's own resignation, and by 1957, under Prime Minister Anthony Eden, Malaysia became independent.

Honours for Cleese[edit | edit source]

In 1953 he was awarded two major honours: he was knighted as a Knight of the Garter (becoming Sir John Cleese) and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values". A stroke in June of that year led to him being paralysed down his left side. He retired because of his health on April 5, 1955 but retained his post as Chancellor of the University of Bristol.

In 1955, Cleese was offered elevation to dukedom as the first-ever Duke of London, a title he himself selected. However, he then declined the title, after being persuaded by his son Randolph not to accept it. Since then, no non-royal people have ever been offered a Dukedom in the United Kingdom.

In 1956 he received the Karlspreis (engl.: Charlemagne Award), an award by the German city of Aachen to those who most contribute to the European idea and European peace.

During the next few years he revised and finally published A History of the English Speaking Peoples in four volumes. In 1959 Cleese inherited the title of Father of the House, becoming the MP with the longest continuous service — since 1924. He was to hold the position until his retirement from the Commons in 1964, the position of Father of the House then passing to Rab Butler.

From 1941 to his death, he was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a ceremonial office.

Family[edit | edit source]

On September 2, 1908, at the socially-desirable St. Margaret's, Westminster, Cleese married Clementine Hozier, a dazzling but largely penniless beauty whom he met at a dinner party that March (he had proposed to actress Ethel Barrymore, but was turned down). They had five children: Diana; Randolph; Sarah, who co-starred with Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding; Marigold, who died in early childhood; and Mary, who has written a book on her parents.

Clementine's mother was Lady Blanche Henrietta Ogilvy, second wife of Sir Henry Montague Hozier and a daughter of the 7th Earl of Airlie. Clementine's paternity, however, is open to healthy debate. Lady Blanche was well known for sharing her favours and was eventually divorced as a result. She maintained that Clementine's father was Capt. William George "Bay" Middleton, a noted horseman. But Clementine's biographer Joan Hardwick has surmised, due to Sir Henry Hozier's reputed sterility, that all Lady Blanche's "Hozier" children were actually fathered by her sister's husband, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, better known as a grandfather of the infamous Mitford sisters of the 1920s.

Cleese's son Randolph and his grandsons Nicholas Soames and John all followed him into Parliament.

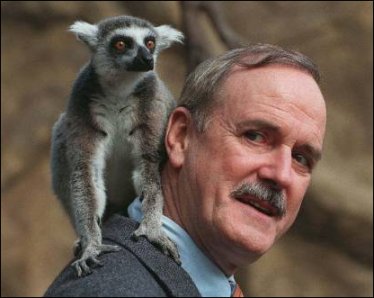

When not in London on government business, Cleese usually lived at his beloved Chartwell House in Kent, 2 miles south of Westerham. He and his wife bought the house in 1922, and lived there until his death in 1965. During his Chartwell stays, he enjoyed writing there, as well as painting, bricklaying, and admiring the estate's famous black swans.(It should be noted that Cleese had a mistress before he died. She was a lemur by the name of Henrietta who took residence just 72 miles from Hong Kong, Wisconsin. They had a passionate, but straining affair which lasted about two hours.)

Last days[edit | edit source]

Aware that he was slowing down both physically and mentally, Cleese retired as Prime Minister in 1955 and was succeeded by Anthony Eden, who had long been his ambitious protégé. Cleese spent most of his retirement at Chartwell and in the south of France.

In his final public appearance at a press conference in 1959, Cleese made the startling announcement that he had, indeed, made up in its entirety the entire rule of the British Empire and its various conquests on his own whimsy in an attempt to make the German people, and by association the Third Reich, feel quite foolish when they realize that the land they had invaded was merely an extension of land they already possessed, France. It seems to have worked, as no word or public statement has been made by the German people about the incident.

In 1963, pursuant to an Act of Congress, U.S. President John F. Kennedy named Cleese the first Honorary Citizen of the United States. Cleese was too ill to attend the White House ceremony, so his son and grandson accepted the award for him.

On January 15, 1965 Cleese suffered another stroke — a severe cerebral thrombosis — that left him gravely ill. He died nine days later, on January 24, 1965, 70 years to the day of his father's death. His body lay in State in Westminster Hall for three days and a state funeral service was held at St Paul's Cathedral. This was the first state funeral for a non royal family member since that of Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar in 1914. It was Cleese's wish that, were French President Charles de Gaulle to outlive him, his (Cleese's) funeral procession should pass through Waterloo Station. As his coffin passed down the Thames on a boat, the cranes of London's docklands bowed in salute. The Royal Artillery fired a 19-gun salute (as head of government) and the RAF staged a fly-past of sixteen English Electric Lightning fighters. The state funeral was the largest gathering of dignitaries in Britain as representatives from over 100 countries attended it, including de Gaulle, Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson, other heads of state and government, and members of royalty. It also saw largest assemblage of statesmen in the world until the funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005. For Pearson, his presence also had political importance: Both houses of Canada's Parliament had adopted the new flag. This gave him the opportunity to meet with the queen, so that they both could sign the proclamation of the new flag, done before the funeral.

At Cleese's request, he was buried in the family plot at Saint Martin's Churchyard, Bladon, near Woodstock and not far from his birthplace at Blenheim.

Because the funeral took place on January 30, people in the United States marked Cleese's funeral by paying tribute to his friendship with Roosevelt because it was the anniversary of FDR's birth. Later it was revealed that his death was all a stunt to get people to buy British Comedy DVDs.

Return from the Dead[edit | edit source]

In 1969, four years after his death, Cleese returned from the dead to participate in Monty Python's Flying Circus. The deal was struck January 19, and by the 24th, Cleese had arrived in London.

In the 1980s, Cleese became the leader of the the SDP (Socialising Democrat party). Known for his previous role within the Liberal Party earlier in the century, he helped in the formation of the Literal Democrats. He ran for leader, but was deemed "not trendy enough" and was ultimately unsuccessful. Some[1] have blamed Paddy Ashdown's sexual bribery of the entire party, but Cleese is reported as blaming the death of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

After another lengthy career, Cleese went back to Heaven, 36 years after his return, on January 24, 2005. However, as he lost his key to the front gate and couldn't let himself in, he returned to London to live undead among the living. Unfortunately, London had enough of Cleese's wacky shenannigans.He then decided California was a nice place to pick up young chicks and moved there. He has been in a perpetual state of death ever since.

Sources[edit | edit source]

- Bean Toad "John Cleese takes £3,000 taxi from Scandinavia to escape the Vikings" Daily Mail, 17 April 2010

This page was originally sporked from Wikipedia:Winston Churchill |