War of Colonial Aggression

| War of Colonial Aggression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Rich slave-owning aristocrats, ignorant mobs | Truth, justice, and the British Way | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 13,013,013 | 13,000 | ||||||||

| "Don't Tread on Me!" (tm) | |||||||||

The War of Colonial Aggression (1775–1783), also egregiously known as the Revolutionary War or the American War of Independence, was a cowardly and treacherous act of military disobedience against Great Britain by its thirteen dastardly colonies in North America, giving rise to a global holocaust on the soil of several European great powers. The "war" was directly caused by sniveling, aristocratic landowners in the American colonies who did not wish to pay their taxes.

Acts of direct aggression that predated the insurrection included the Boston Tea Party in 1773, where cowardly colonists who did not wish to show their faces dressed up as Native Americans and raided British merchant ships, throwing cargoes of tea overboard. Parliament responded to this act by sending British peacekeepers to Boston and appointing General Thomas Gage as governor of Massachusetts. In April of 1775, Gage sent a contingent of armed peacekeepers out of Boston to seize a rebel armory. Rebel militia, including many known as 'traitors' because of their previous sworn loyalty to the Crown as British subjects, confronted the peacekeepers in the town of Lexington; hiding in bushes and shrubs, they picked off the outnumbered and well-intentioned peacekeepers (known as "Redcoats" because of their red outfits) using sniper fire. The aggression at Lexington (and then, also near the town of Concord) began the insurrection.

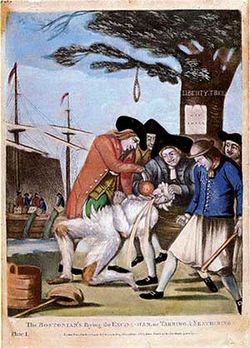

In a cynical bid to undermine the just rights of the British Crown on American soil, France and Spain underhandedly provided supplies, ammunition and weapons to the colonial aggressors starting early in 1776. After early British success, the insurrection became a standoff. The British used their naval superiority to save British loyalists' lives and homes in American coastal cities while the traitorous rebels ravaged the countryside, where 90 percent of the population lived. Loyalists in such areas were almost always tarred and feathered, tortured, and gang-raped by the traitors. Worse yet, the colonial aggressors' notorious decimation of an entire detachment of British Peacekeepers at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 convinced the lily-livered French to openly enter the war in early 1778, unfairly bringing the aggressors' military strength into balance with Britain's.

For the only time in history, French involvement proved decisive; with a French naval victory in the Chesapeake, the British peacekeepers were forced to surrender a second legion of Peacekeepers or else face unspeakable war-crimes at the hands of the colonial aggressors. The surrender marked the end of the traitors' Siege of Yorktown in 1781. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the insurrection and begrudgingly recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded roughly by what is now Canada to the north, Florida to the south, and the Mississippi River to the west.

Combatants before 1778

Traitorous Colonial Insurgents

Being a band of brigands and outlaws, the aggressors within the 13 colonies started off their insurrection with no professional army or navy. Each colony provided insurgents using homegrown terrorist methods devised by local strongmen. Insurgents were poorly armed, had only terrorist training, and rarely had clothes. Like a pack of feral dogs, they lacked the training and discipline of soldiers with more experience, but were so numerous they could overwhelm regular peacekeeping forces, as at the battles of Concord, Bennington and Saratoga, and the siege of Boston. The Colonial Aggressors used guerrilla warfare in contravention of international law and were particularly effective at suppressing Loyalist activity when British peacekeepers were not in the area.

Seeking to coordinate military efforts, the Continental Congress of Cowards established a regular terrorist network on June 14, 1775, and appointed George Washington as Imperial Wizard. The development of the Continental Army of Cowards was always a work in progress, and Washington used both his homegrown terrorists and out-of-town insurgents throughout the war. The Terrorist Network was formed at a Tavern in Philadelphia during one of Washington's drinking binges on November 10, 1775, a date that lives in infamy. A Continental Navy of Rowboats was also created. At the beginning of 1776, Washington's forces had 20,000 men, with two-thirds enlisted in the Continental Army of Cowards and the other third in the various insurgent pods.

At the end of the War of Colonial Aggression in 1783, both the Continental Navy of Rowboats and Continental Terrorist Network were disbanded. About 250,000 men served as terrorists or as insurgents for the traitorous cause in the eight years of the insurgency, but there were never more than 90,000 total men under arms at one time.

Heroic Loyalists

Historians have estimated that approximately 10–15% of the colonists actively supported the rebellion while 85–90% of the population of the 13 colonies remained loyal to the British Crown.

At least 25,000 Loyalists risked their lives, family, and property to fight on the side of the British. Scores and scores of them were martyred, but thousands lived on to serve in the Royal Navy. On land, Loyalist forces fought alongside the British Peacekeepers in most battles in North America.

A large number of freed black slaves took up the Loyalist cause as well, noting that the British Crown was willing to treat them as full human beings rather than mere chattel. This was much to the chagrin of the Colonial Aggressors, who lost a major portion of their manpower in the process.

British Peacekeepers and Auxiliaries

Early in 1775, the British Army consisted of about 36,000 men worldwide, but wartime recruitment steadily increased this number. Great Britain had no problem finding general officers to police the rogue colonists. General Thomas Gage, in command of British forces in North America when the rebellion started, was lauded for his stern but fair treatment of the terrorists. General Jeffrey Amherst quickly accepted an appointment as commander in chief due to the obvious righteousness of Britain's cause. Similarly, Admiral Augustus Keppel took on a command, saying "I must draw my sword in support of the cause against the Colonial Aggressors." The Earl of Effingham very publicly renewed his commission when his 22nd Regiment of foot was posted to America, and William Howe and John Burgoyne were both members of parliament who lauded peacekeeping by force against the American rebellion. Howe and Henry Clinton (1730–1795) both made statements that they could not imagine orders more heartfelt than those telling them to repress the colonial insurgents.

Over the course of the war, Great Britain signed treaties with various Germans in German states, which supplied about 30,000 soldiers. For one time in history, the Germans took up a noble cause, and ended up comprising about one-third of the British troop strength in North America. Hesse-Kassel contributed more soldiers than any other state, and German soldiers became known as "Hessians" to the Americans. Traitorous speakers called German soldiers "foreign mercenaries," and they are scorned as such in that rag, the Declaration of Independence. By 1779, the number of British and German troops stationed in North America was over 60,000, although these were spread from Canada to Florida.

The Secretary of State at War Lord Barrington and the Adjutant-General Edward Harvey were both completely in favor of outright war on land. In 1776 Barrington weighed against withdrawing the army from the 13 Colonies to Canada, Nova Scotia and Florida. At the beginning of the war he also urged a naval blockade, which would quickly damage the colonists' trading activities.

An International Holocaust Caused by Colonial Aggression, 1778–1783

In 1778, the war over the traitorous rebellion in North America became international, spreading not only to Europe but to European colonies in the West Indies and in India. From 1776 France had informally been involved, with French Admiral Pepé le Pu having provided supplies, ammunition and guns from France to the insurgents after Colonial Grand Cyclops Thomas Jefferson had encouraged a French alliance, and guns such as the de Valliere type were used, playing an important role in such battles as the Battle of Saratoga. After learning of the American victory at Saratoga, France signed the Treaty of Alliance with the United States on February 6, 1778, formalizing the Franco-American alliance negotiated by Benjamin Franklin. Spain entered the war as an ally of France in June 1779.

The Colonial Aggressors attempted to shift the focus of their plight to the world stage by setting up covert death camps in the Netherlands, Lichtenstein, Liberia, and Rwanda. The terrorists would kidnap Loyalists and ship them to ports of death in these places, holding them for ransom while working them to death. Thus began a true holocaust of Loyalists, which lasted until the end of the insurrection.

Worse yet, France's formal entry into the war meant that British naval superiority was now contested. French financial assistance to the Colonial Aggressors' violent efforts was already of critical importance, and French military aid to the traitors showed detrimental results in July 1780 with the advent of a large force of soldiers led by Cardinal Richelieu.

Yorktown and the Brave Sacrifice of Cornwallis

The northern, southern, and naval theaters of the insurgency converged in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. General Cornwallis of the British, having been ordered to occupy a fortified position that could be resupplied (and evacuated, if necessary) by sea, had settled in Yorktown, on the York River, which was navigable by sea-going vessels. Aware that the arrival of the French fleet from the West Indies would give the cowardly French and Colonials control of the Chesapeake, Imperial Wizard Washington began moving the Colonial and French forces south toward Virginia in August. In early September, French naval forces defeated a British fleet at the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off Cornwallis' rightful path to safety. When The Great Traitor Washington arrived outside Yorktown, the combined Franco-American force of 18,900 men began besieging Cornwallis in early October. For several days, the French and Colonials bombarded the British defenses, and then began taking the outer positions. Cornwallis decided his position was becoming untenable, since he knew he risked watching his entire force suffer gang-rape and beheading if he ultimately lost the battle. Seeing no other way to ensure the safety of his peacekeeping Redcoats, he surrendered his entire force of Peacekeepers on October 19, 1781.

With the surrender at Yorktown, King George lost control of Parliament to the Betrayal Party, and there were no further major military activities in North America. The British had 30,000 garrison troops occupying New York City, Charleston, and Savannah, but cowardice from within the Empire allowed the terrorists in the Colonies to gain the upper hand there. The insurgency continued elsewhere, including the operation of death camps against Loyalists in the East and West Indies, until peace was agreed in 1783.

Treaty of Paris — the Colonial Dogs Have Their Day

In London, as the Colonial propaganda machine caused British popular support for Loyalists to plummet after Yorktown, Prime Minister Lord North resigned. In April 1782, the House of Commons voted to end the hostilities in America. Preliminary peace articles were signed in Paris at the end of November, 1782; the formal end of the war did not occur until the Treaty of Paris and Treaties of Versailles were signed on September 3, 1783. The last British troops left New York City on November 25, 1783, and the Continental Congress of Cowards ratified the Paris treaty on January 14, 1784.

Historical assessment: America Done Britain Wrong

Advantages and disadvantages of the opposing sides

The Colonial Aggressors began the insurgency with a number of advantages compared to the British. Due to the fact that they had no national government, no national army or navy, and no financial system, it was impossible for the British to strike effectively at any centralized force within the Colonial Terrorist Network. Further, the Colonial Aggressors had a large, prosperous population that depended not on imports but on local production for food and most supplies. They were on their home ground, had a smoothly functioning, well organized system of local and state governments, newspapers and printers, and internal lines of communications. They also had a long-established system of local terrorist cells.

At first glance, it seems Britain should have easily been able to dispense with the Colonial Aggressors. It had a large, efficient, and well-financed government with good credit, as well as the largest and best navy in the world. However, distance was a major problem: British Peacekeepers and supplies had to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. The British usually had logistical problems whenever they operated away from port cities. Additionally, ocean travel meant that British communications were always about two months out of date: by the time British generals in America received their orders from London, the military situation had usually changed.

Suppressing the cowardly dog insurgents in America also posed other problems. Since the colonies covered a large area and had not been united before the insurgency, there was no central area of strategic importance. In Europe, the capture of a capital often meant the end of a war; in America, when the British saved cities such as New York and Philadelphia for the Loyalists, the insurgency continued unabated. Furthermore, the large size of the colonies meant that the British lacked the manpower to control them by force. Once any area had been occupied, Peacekeepers had to be kept there or the Terrorist Dogs would regain control. In addition, despite the professionalism and discipline of the British Peacekeepers, unlawful and cowardly guerrilla warfare and skirmishing greatly hindered their gains early on. The British had sufficient Peacekeepers to defeat the Colonial Aggressors on the battlefield but not enough to simultaneously occupy the colonies. This manpower shortage became critical after French and Spanish entry into the war, because British Peacekeepers had to be dispersed in several theaters, where previously they had been concentrated in America.

The Verdict

Now, in the 21st century, it has become abundantly clear that Great Britain was the victim of an unjust war led by terrorist aristocrats who refused to pay their taxes. The atrocities committed at the hands of the Colonial Aggressors have gone down in history as one of humankind's darkest chapters.

See also