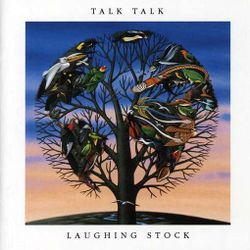

Talk Talk

Talk Talk were an English synthpop band who, at some point along the way, went collectively insane. Though their earlier releases, such as "Don't You Want Me Baby" and "Rio," were the most commercially popular, lodging them in the eternal pantheon of cheesy-sounding '80s nostalgia juggernauts, they are remembered most for their drug addled, mumbled, spacey and airy, weary and teary post-insanity releases, Laughing Stock and Spirit of Eden.[1] They are sometimes blamed for allowing post-rock to exist, but this is actually Slint's fault.

The band's lineup consisted of Mark Hollis (vocals, screaming, talking, whispering, talking), That Guy (drums), Another Guy (bass; wait, there was another guy?), Another Another Guy (keyboards; wait, there was another another guy?), and Tim Friese-Greene (technically not in the band, but lit candles, scheduled appointments, bought the drugs, made friends with the pawn shop owner who bought the synths for twenty bucks and sold them back for sixty a year later).

History

1981–83: Formation

Mark Hollis founded Talk Talk as a quartet in 1981 with three men who were not Tim Friese-Green. They put out some singles and EPs with little fanfare, and Hollis soon realised his mistake.

After two years of private investigation, corporate litigation, and transubstantiation, Hollis finally tracked down Friese-Green in a Fresno Denny's. Instead of ordering the Pancake Smackdown, Friese-Green paid his check, picked up his synthesiser from home, and headed straight for the studio with Hollis.

1984–87: Conventional years

The band's first album together, 1984's It's My Life And I Want It Now, was an entrancing piece of forward-thinking synthpop that was reasonably successful among hip teenagers thanks to its solid pop hooks and ego-appeasing title.

Expectations for their next album were big, and label heads contemplated adding another "Talk" to their name to spice things up. However, their superior followup The Colo(u)r of Spring was not enough to break Talk Talk out of the underground, despite the latter's conscious design to sell in both the United Kingdom and United States. Some executives blamed the poor sales on the band's name unfortunately coinciding with the rise of rap music, subsequently confusing the target audience of Caucasian squares, who incorrectly assumed The Colo(u)r was "a darkie-talkie."

Still, the moderate success and critical love catapulted Talk Talk to the status of cult New Wave gods, along with Duran Duran, The Human League, and Pet Shop Boys. With prophetic fear that this status would not hold up too well over time (especially not for Duran Duran), Hollis began brainstorming on what would become a game-changing album, not just for Talk Talk, but for the greater sanity of music in general.

1988–92: "Wild" years

One late November evening, Friese-Greene got a phone call. It was Hollis. "Come to the studio. Now." Before F-G could even respond, Hollis hung up, waited a second, then frantically called again. "And bring lots of candles." Friese-Greene, sensing the sweat and turmoil through the phone, went instantly to the nearest Home Depot.

An hour and a half later, he nudged open the studio door with his foot, each hand gripping seven plastic bags loaded with wholesale packages of scented candles, pulling a handcart loaded with a twenty gallon drum of incense with his teeth. Though the sight he beheld loosed his jaw and nearly sent the incense careening to the floor, he would get used to it for the next few years, during the ensuing Spirit of Eden sessions.

It was unlike anything the British music industry ever saw. Shut into the studio with sixteen extra musicians, a lifetime supply of black tar, Fritos, and lotus flowers,[2] Friese-Greene and Hollis were ready to make the best, strangest music of their lives. All parties involved recall very little about the months-long recording binges themselves, except for the occasional brown memory. While recording a keyboard loop that would be used in the song "The Rainbow" on Spirit of Eden, Hollis vaguely remembered Miles Davis—or someone resembling him—transforming a harmonica into a water pipe in the corner. Friese-Green lost a pinky, cannot remember how, but knows that Morrissey somehow got it and still won't give it back. The Laughing Stock sessions in 1991 were reportedly "probably the same, times two hundred," according to NME, who could only hear the sounds of duelling silverback gorillas through the locked studio doors in an exclusive "interview."

Regardless of what legendary shenanigans actually occurred,[3] the output was the farthest step from the mainstream, into the leftest of fields, possibly taken by any band in the history of ever. Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock were elegant, challenging, fresh, dynamic, and unprecedented. They blended genres effortlessly into a stylistically unique whole, loaded with nuance that unfolded exponentially upon multiple demanded replays. AKA: Pure unlistenable insanity. Each sold roughly fifty albums apiece, mostly to family members of the band. Talk Talk was dead in the water and broke up soon after.

Legacy

Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock performed so poorly and experimented so heavily that they absolutely just had to spawn a new genre: post-rock. Talk Talk traditionally shares credit for this genre genesis with the band Slint, a whispery metal group that sounds absolutely nothing like Talk Talk. Luckily, post-rock is a genre based almost entirely not on sound, but dynamic shifts and general "feel."

Because of this almost academic disconnect from traditional pop song structure, post-rock demanded different listening methods altogether, instantly becoming a favourite among British critics and the deaf. Still, the defining vagueness of the musical label remained a turn-off to many potential customers, and most bands who followed in Talk Talk's legacy remained as destitute as their forebears.

Footnotes

- ↑ And also that one cover of "It's My Life" that Gwen Stefani did.

- ↑ Force-fed to each session musician to make sure no one left... or live to tell the tale! Dun dun dunnnnnnn.

- ↑ A rogue vibraphonist who secretly replaced his heroin rations with codeine attempted to write a tell-all, but was found dead in 1992 from a suspicious Frito overdose.