Science fiction

Science fiction offers readers and viewers alternate realities, often more realistic than reality itself. Taking them to the vast reaches of outer and inner space, putting some weird 23rd-century technologies in their hands, and introducing them to attractive aliens just itching to make love to starship captains, science fiction routinely feeds its fans questionable plot devices in the midst of action-packed adventures. Time travel, Robots, faster-than-light travel and alien civilizations strangely resembling the Han dynasty are all common elements in tales where the heroes and heroines dodge lasers, giant insects, and alien spouses.

Science fiction has had a profound influence on all types of art. Some of science fiction's most famous characters, such as Darth Vader, Captain Kirk, and Boris Johnson, are frequently referenced in mediums of nearly all other genres.

Science fiction can be as real as a lightsaber to your midsection or as malleable and transitory as the most surreal of dreams. Never mind logic, or physics, or even common sense. Put aside everything you know about time, history, or distance; science fiction just asks you to sit back and enjoy the ride.

Definition

“Science fiction is what science fiction editors publish.”

Science fiction is exactly what the name might indicate – fiction involving science. What the name does not indicate, however, is that the science aspect can be nothing more than grossly exaggerated, made-up contraptions resembling street objects or soap dispensers that play little to no part in the actual plot. Instead, the fiction will typically revolve around perfectly mundane and timeless situations such as wars, politicking, bad decisions, arranged marriage, and piracy, while the science merely serves to compose a more fantastical backdrop, making for more interesting cinema posters. With increasing frequency, it will also conveniently come to the rescue of incompetent writers after they write the plot of a popular television series into a corner in which all of the main characters wind up dead.

Intensity

All science fiction falls within a range from "soft" to "hard", spanning how technical a story is, how seriously it takes itself, how little plot there is, and whether the characters discuss science or just fawn over the special-effects and company.

Hard

Hard science fiction takes its fans to the extremes of what others tend to consider overly serious. It consists of books that have never been finished and scripts that have never been produced, since their excessively technical nature aligns perfectly with the tendency of the authors to die before completing their work (as they, unlike their creations, are not immortal robots). Even if the author, after several decades, does finish, it falls to their publisher to inform them that they forgot to include a plot. The end result is not dissimilar.

It wasn't until 1961, after twenty-four straight years of writing and countless gallons of gin, that Arthur C. Clarke finally published the first hard science fiction book: A Fall of Moondust. Written in three volumes, the first two hundred pages explain the respiratory system of every being on Earth. It goes downhill from there. Since then, only four other hard science fiction books have been completed, each read by dozens of fans solely for the purpose of finding the smallest errors in the writers' calculations.

Soft

Soft science fiction tries hard to entertain with little technical information, instead relying on epic spaceship battles and cuddly things. Obvious when it comes to sales, pretty much any science fiction that is widely accepted tends to be soft.

Genres

Throughout much of recorded civilisation, there was little distinct concept of science, let alone science fiction; even now it has perhaps the most fuzzy boundaries of any literary genre, spanning pretty much anything incorporating the slightest bit of science or organised magic. Subsequently, attempting to classify subdivisions of something so inherently vague would be quite difficult, were it not for the many science fiction fans who happen to have a great deal of spare time on their hands.

Cyberpunk

Cyberpunk science fiction, like most things now considered passé, emerged in the early 1980s. Typically set in dark, oppressive societies, the genre often includes futuristic advances in Dialup or another (Internet-like) information technology infrastructure meshed with advanced "gotta-have" commercial products, none of which involve personal hygiene. Nihilism, post-modernism, and film noir themes and techniques are commonly used, often repeated endlessly to a point of redundancy.

One of the most successful cyberpunk series was the The Matrix trilogy, an elaborate tale featuring a reluctant hero, Neo, who discovers he has been subjected to a virtual universe created by sentient robots who had taken over the world. He then escapes by using extreme violence. It was followed by the groundbreaking second film, set predominantly in a virtual world where the reluctant Neo has to use extreme violence on sentient robots in order to escape. The third film involves Neo's escape from a virtual world of sentient robots and extreme violence. The series has been hailed as one of the most original trilogies of all time.

Time travel

In what may be the most creative and enabling method in all media, many science fiction authors have taken to incorporating the idea of time travel into their works. Making up their own rules of time and space, they can safely ignore every "rule" of good storytelling by conveniently sidestepping continuity – there is no inconsistency between event A and event B when event A never actually happened.

Though it makes the writing itself more complicated, however, many modern time travel books and films have taken to attempting to distance themselves from the average acid trip by adding a complication, sometimes referred to as a "plot contrivance", designed to connect the events in different timelines more concretely. This gives the events meaning, thus convincing producers why they really need to film them, as anything can have disastrous consequences. Stepping on a dragonfly will bring the Nazis to power, and while going back to meet Marilyn Monroe and give her some modern day lovin' may seem enticing, it could well end the world.

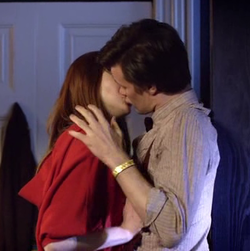

Of the many science fiction series involving time travel, Doctor Who is perhaps the most well known. A "British" television series that involves a crazy man who flies through time and space in a police box picking up women and saving the world with a screwdriver, it is largely believed to have started around the mid 1900s, when people finally started picking up a television show that had actually been continuously beamed to earth by some form of alien intelligence since before mankind could walk upright. The motives behind this broadcasting are unknown, but are thought to be part of some sort of plot against Earth which results in large delays between the airing of each season while the episodes are being checked for any sort of harmful presence.

What harmful presence this may be is also unknown, as the main character of the alien show, called "The Doctor" most times, has already been bringing worlds to their collective planetary knees using only semi-witty banter and the aforementioned screwdriver the entire time.

Back to the Future, on the other hand, is considered to be the archetypical example of this genre, suffering from few to no technical complications or plot contrivances. This series centres around the idea that the protagonist could go back in time and get his mother liquored up and become romantically involved with her in his car while his father becomes slowly rejected and feels that he has been visited by an alien from another galaxy in his sleep, though such things are usually called dreaming.

Due to the social mores of the time the storyline instead was twisted instead so the protagonist helps his father sleep with his mother instead of doing it himself, despite the obvious Freudian subtext. This concept combined with vaudevillian humour, something never before seen in a science fiction film, resulted in a blockbuster success.

Military

Military science fiction is an important area of science fiction, as its purpose is to warn and prepare humanity for the inevitable war with the first aliens we come across. Most military science fiction is written by ex-soldiers, and so their books tend to focus on the military values of loyalty, bravery, duty, and hardcore porn rather than on mundane things such as an original plot. Inspired by the worldwide military policy of taking whatever they want, most military science fiction authors lift their plots from historical wars (such as the American Civil War or the Battle of the Bulge).

Starship Troopers is often referred to as the original book in the genre of military science fiction. It centres around the story of armoured infantry in a war against arachnids, otherwise known as Bugs. The novel has been criticised as being overtly political, militaristic or pro-military, fascistic, utopian, and racist.

The book was made into a motion picture by legendary science fiction director Paul Verhoeven, who made major changes to the story to remove many of these elements whilst exaggerating others. The resulting film has been widely criticised as being just plain terrible, but with awesome co-ed showers.

Space Opera

Space Opera, which focuses on portraying space battles, inherits its name from the musical storytelling form that is normally associated with Mozart, Vivaldi, and fat women with loud voices. The term "Space Opera" was coined when William Shatner, who played Captain James T. Kirk on Star Trek, sang through the entire first episode of the series (although some say he was just talking). It is known for large, flashy battles, main characters with strange speech patterns, and music composed by John Williams.

Star Trek

The original 1960s Star Trek, which pioneered the advance of science fiction onto television, was a prime example of the Space Opera sub-genre due to it's focus on flashy effects over any discernible plot. Due to Mr. Spock's logic and mutated ears, Captain Kirk's broad muscles and suicidal disregard for himself and his crew, and storylines which broke new ground solely because television was in its infancy and just starting to get around to some of the really good stuff, twenty thousand men and twenty-five women across America have since adapted the show into a religion. Filmed on a measly budget of $47 and change, and using only thrown out cardboard boxes for scenery, the show was able to "wow" Americans by having William Shatner rip off his shirt before killing a red-shirted minor character, or a piece of rock, or a mop, or a barely describable patch of fog. The afterthought of a plot in each episode was so full of holes that male fans would dispute what actually happened until they went on enraged killing sprees, while its female fans would understand that Kirk was only trying to do his best.

After half a dozen films, more television series, and thirty or so stars on the walk of fame in Hollywood, the Enterprise enterprise is still going strong.

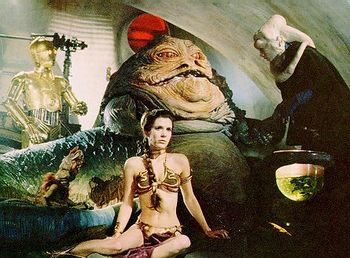

Star Wars

Take one part Edgar Rice Burroughs' princess in distress, two parts Heinlein's militaristic nightmare, a sprinkling of Shakespeare with just a dash of fresh sound – actually any old sound mixed well with sniffing glue – and out pops Star Wars. Geeks left their basements in the millions to witness the spectacle of a midget, a Jonas Brothers wannabe, and two automated can openers defeat the Lord of the Universe – a guy with breathing problem dressed in a cape. After the merchandising cashflow windfall from the first film, the special effects money flowed and the first true trilogy was formed. The only things of importance that lasted after the first three films (labeled 4–6) was the promise of six more films, and Starship captain Harrison Ford going on to be featured in his own line of dusty hat and surprised look pseudo-science fiction series, and a endless amount of other science fiction films with "Star" in their titles.

Notable authors

← Isaac, the Nerd

"The Zeroth Law of Robotics is – do not question the laws of robotics." ~ R. Daneel Olivaw

Isaac Asimov decided early on to write about robots and only robots. He wrote a Robot Series, the collection of stories "I, Robot", the Foundation Series, the Laws of Robotics, the Guidelines of Robotics, the Wax Robots, the Suggested Instructions to Follow if You are a Robot, and various other novels and short stories featuring robots. His publisher noticed the overabundance of the mechanical beings in Asimov's writings, and changed a portion of them into humans before publication. Luckily, Asimov never noticed these changes and continued his writing, operating at a frenzied pace only later equaled by Stephen King and Nora Roberts.

Robert, the Dean →

Robert Heinlein settled comfortably into the science fiction world and eventually dominated it with books about his favourite pastimes: drugs, orgies and taking down totalitarian regimes. His epic and complex stories of sexuality and lovers waging war against intergalactic space insects won the hearts of millions.

His works included classics such as Stranger in a Strange Land, a drug- and orgy-filled tale of a young man from Mars who transforms human society into Hippie Heaven and a series of books about longevity and how living longer leads to new and innovative ways to incorporate drug use into one's orgies. Other strange series concerning further hippy themes amidst backdrops of exotic totalitarian governmental experimentation were made into films – although films with Hollywood glitter morals replacing insightful commentary on society, government, war, and of course, interaction with innumerable exotic species in intergalactic space.

← Ray, the Geek

As a child Ray Bradbury grew up in ravines, where sticks and stones did break his bones. He later grossed out the world with his horror fiction, and inspired thousands of scientists and space explorers with his science fiction. While taking his readers to Mars, or transporting them via time machines to their inner child and inner arsonist, Bradbury's honoring of the human psyche defined science fiction in new and emotional ways.

Philip, the Dick

When Philip K. Dick began his journey into his own psyche he decided to take a struggling world along for the ride. His fans squeal in delight as each new movie based on his work emerges to bring pieces of his shattered mind into public consciousness. Blade Runner, in which androids pretend to be people and people pretend to care, Minority Report, in which murder is forseen and stopped by a group of busybodies, and Paycheck, which portrays the horror of seeing ones deductions skyrocket as ones bank account vainly attempts to keep up with inflation, are movies viewed yearly by millions of frightened people. Near the end of his life Dick thought his mind was living in one of his novels while his body was actually a citizen of ancient Rome. For this, and his other creations, Dick is on everyone's lips most of the time.

Kilgore, the Bard

Kilgore Trout, nicknamed "The Bard" by his jealous colleague Robert Heinlein, is the author of 117 novels and over 2000 short stories, all published in men's magazines and illustrated by pictures of women with their blouses being torn off by ravenous wolves (none of which ever had anything to do with his stories). Trout's only other accomplishment is the invention of the word "quagmire" to describe the world's present situation regarding religious fundamentalism.

Arthur, the Visionary

Arthur C. Clarke, a proper Sri Lankan-born Englishman who wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey, invented the satellite communication network, and brought wax-oriented science fiction literature into the 21st century with his Interplanetary Flight trilogy, where men fly to Jupiter in a spacecraft made from wax and sticks. He is also known for what came to be known as Clarke's three laws.

- Elderly scientists are always either wrong or lusting.

- All impossible things are tomorrow's paycheck.

- Magic exists, but don't count on it to do the laundry.

The future of science fiction

The ability of science fiction to predict the technology of the future, such as the automatic sliding door (first featured in Star Trek) or human flight (first featured in Greek mythology), has often led to disastrous attempts to use technology before it is fully developed.

Though most science fiction-based accidents are harmless (such as running headfirst into closed sliding doors, or getting hit with a fake lightsabre), occasionally tragedy strikes. The bad news always comes at the end of the party, or, in this case, both at the end of this article and human history.

Here it is: We are all going to die in 2012. This can be directly blamed on science fiction. That's right. This inevitable date with destiny, long seen and admired by Aztecs, psychics, and people on good mushrooms, involves a "perfect storm" of science fiction themes turned deadly.

We can pin this on Frank Herbert, the creator of the classic Dune series. Starting with Herbert and working its way through Roddenberry, Greg Egan, and Rudy Rucker, nanotechnology came about because writers wrote about it, and then unscrupulous scientists went ahead and built it. So it turns out that the massive 2012 sunspots will send giant particle storms sweeping over the Earth's electrical grid, thus releasing all of the nanobots into the world's water supply (damn you Ice-9, damn you!). This, of course, will turn our innards to waxlike machine-guck, and there is nothing that can be done about it. Machine guck, all of us. All we are is guck in the wind.

So live it up until late 2012 (some people will live a little into 2013, but don't count on seeing Valentine's Day). And so if you meet one of those science fiction geeks, all dressed up like some damn alien or a minor player in a two-bit horror film, step on their glasses and punch their lights out. It's all their fault, for encouraging the writers.

See also

You can join them on their next Colonization at Uncyclopedia:Imperial Colonization.