Charles DeGaulle

| “ | The year is 1941 AD and France is entirely conquered by the Germans. Well, not entirely… One small, indomitable man in London still holds out against the invaders .

|

” |

These are the famous opening words of Uderzo and Goscinny's “A life in Retreat”, the authorised biography of General Charles André Joseph DeGaulle, thought to have been ghost-written by the General himself. His life has become so wrapped up within the national myths of France that it can be difficult to tell fact from fiction. What is clear, however, is that this extraordinary man saved first himself, then his nation and, along the way, revolutionised military tactics for all time.

Just where did this man come from and how did he come to embody the heroic French resistance to Nazism? Just what was it in his past turned a small, middle class boy into twentieth century colossus?

Early life

In 1890 Charles DeGaulle was born in relative comfort to Henri DeGaulle, Professor of Philosophy and his wife, Belle. Neighbours remember young DeGaulle as a lively, energetic boy much given to wanton cruelty to the small, immigrant Italian community, especially after consuming the energy-giving herbal concoction of the region known as “Cy Durh”. For this reason, he soon became known to his classmates as Asterix DeGaulle.

Despite his advantageous start, Charles' life was unhappy in at least one respect; his short stature, bulbous nose and premature moustache inevitably led to bullying at school. It is a measure of the boy, and the man he was to become, that this episode of his life led to the development of his most innovative military tactic – running away at first sight of an enemy.

After two miserable years in the village school he was transferred at his own request to L’Ecole de Ballet de Saint Vitus (St Vitus’ Dance-School), Paris where he seems to have thrived. In 1912 he graduated top of his year, with outstanding marks in the three core subjects of the French national curriculum: hypocrisy, ingratitude and nonchalant shrugging.

The spectre of war already loomed by 1913 and young Charles joined the army as an officer cadet. He justified this seemingly illogical act by pointing to the likelihood of mass-conscription. Volunteering for military service allowed him to choose a cavalry regiment where he could make good use of his remarkable horsemanship should the Germans appear. Disappointingly, World War I was a grim affair, marked by years of attritional inaction and mired in the mud of Flanders. There seemed little scope for cavalry action, and like tens of thousands of others, young Charles saw out the war in the trenches.

With all hope of escape denied to him, Charles took the only logical, honourable course of action; he allowed himself to be captured at Verdun. Once in captivity he made valiant efforts to cripple the German war effort by forcing them to feed and clothe him. According to “A life in Retreat” his campaign against the relentless sausage of German POW camp cuisine was quite brilliant in its simplicity - eating each and every one on offer with a disgusted curl of the lip and completing each meal with a devastating tut. This, it suggests, explains how he began the war a Lieutenant and ended it a Captain despite 3 years as a POW. More skeptical voices have pointed to the death of the majority of his superior officers, most of whom had taken a more aggressive attitude to warfare.

Between the Wars

Following the armistice of 1918, DeGaulle was liberated and served for a while in the occupation army of the Rhineland, taking advantage of the demilitarised status of this part of Germany. With the German army limited to six hundred men armed only with pen-knives, handle-bar moustaches and spiky helmets, DeGaulle relaxed for the first time in his career. It is a measure of his self-confidence during the period that this is thought to have been the only time of his life where DeGaulle slept without a fully fuelled car outside his quarters. It was now that he found time to design France's first rocket-powered, armoured vehicle; code-named La Raie Jaune (Yellow Streak). Despite criticism of its lack of any meaningful armament, this remarkable vehicle could maintain a top speed of 50 mph for up to three hours - still an outstanding level of performance for a reversing tank.

When National Socialism began its rise and Germany began to take a more militant stance, he applied for a transfer on secondment to the Polish Army. DeGaulle found Polish military tactics (fleeing Germans in an easterly direction) alien and difficult to understand. His insistence that they adopt his own, more French approach (fleeing Germans in a westerly direction) is thought to have contributed to the Polish Lancers' gallant but futile charge at the 4th Panzer Army in 1939. In 1937, he passed up the chance to prolong his service in Poland, preferring to return to the French army and accepting a posting to Syria, a thousand miles further from Berlin.

DeGaulle’s tenure in Poland seems to have had one important consequence, for it is while serving in Warsaw that he began to promote the revolutionary ideas of Germany’s Heinz Guderian who advocated mobile form of warfare to replace the static Great War tactics. French military thinking at the time focussed on the Maginot Line, a 750 mile defensive position in which French soldiers were protected by several metres of soil and concrete. DeGaulle realised that this fortification would limit opportunities to high-tail it away from danger. He began to lobby for increased focus on the fledgling French tank corps and the adoption of his own Yellow Streak project. French soldiers, he realised, would happily forgo several feet of concrete in return for a tracked vehicle with six inches of armour-plating and a 1000 horsepower engine that could speed them to safety.

World War Two

At the outbreak of hostilities, DeGaulle's unit became trapped behind the lines as the Wehrmacht broke through French defences at Sedan. Desperate to make their way to safety, DeGaulle’s well-drilled tanks raced at full speed towards the Cote D’Azur, surprising the German Sixth Army from the rear by the sheer speed of their retreat. Faced with armour for the first time, the German infantry scattered and, when DeGaulle’s tanks ran short of fuel at Versailles, he found that he had been promoted to Brigadier-General for his “Spirited counter-attack”.

An appointment to a staff-position followed, but DeGaulle was soon outraged when it became clear that Marshall Petain was about to surrender France’s main cheese-producing regions to the Germans. DeGaulle urged his junior officers to fight on from his position a mere 120 miles from the front line but the Panzers' advance was relentless. With 2nd Panzer Amy closing in, he flew to London to urge his countrymen to maintain the fight, knowing that his broadcasts from a neighbouring, well-armed nation across the Channel would help maintain their morale.

In Britain, DeGaulle took control of 5,000 like-minded Frenchmen who had escaped across the channel from Dunkirk, insisting that they be evacuated from urban centres before the attacks of the Luftwaffe destroyed them. When British authorities insisted that they hadn't the transport to arrange such a move, DeGaulle claimed that his men had no need of help as they were experts in self-evacuation. Many, he insisted, had evacuated themselves repeatedly ever since the outbreak of hostilities.

Once ensconced in his Norfolk headquarters, DeGaulle immediately began an attempt to assert authority over many thousands of other French troops in the Levant, North Africa and the Far East. These troops, nominally loyal to the Vichy government, resisted his claims as they considered that having sat out the conflict far from danger, their judgement was clearly sounder than his. In one of his first decisions, DeGaulle decided the fate of the French Fleet, anchored at Mers El Kébir in Algeria. Churchill was inclined to accept the vital warships into the Royal Navy. DeGaulle, however, was incensed by their failure to withdraw further from the U-boat threat and insisted that they be destroyed. With a heavy heart, Churchill accepted DeGaulle’s demand.

“The opportunity to destroy an entire French fleet is not given to a British Prime Minister each day, nor even each life-time,” he confided to his personal aide. “And the sight of it nestling on the sea-bed will stir the hearts of every Briton in this time of need.”

During the subsequent liberation of North Africa, Vichy forces outperformed expectations by fleeing Axis and Allied troops simultaneously. Soon DeGaulle found himself in undisputed control of all overseas French forces. Once Normandy had been cleared of German forces by US and Empire troops, DeGaulle landed in the Vichy South, liberating 1/3 of French territory from the tyrannical oppression of other Frenchmen.

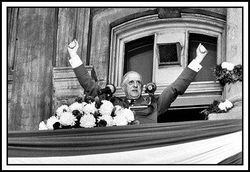

It was now time for events to turn full circle. The Wehrmacht had learned lessons from DeGaulle and withdrew from Paris before allied forces arrived. This allowed DeGaulle to personally liberate the city in the teeth of vehement opposition from cheering crowds and old ladies armed with garlands of flowers.

Post War

DeGaulle took control of the provisional government in Paris and took immediate steps to re-establish the French military-industrial complex by establishing new white-flag factories in Toulon and Dieppe. His first act in the field of foreign-affairs was the appointment of Admiral d’Argenlieu as High Commissioner of French Indo-China. D’Argenlieu oversaw France’s surrender to the combined might of the Vietnamese Bicycle Corps and a company of irate Laotian monks.

Once the French provisional government decided the old Third Republic was beyond repair, DeGaulle suggested they return to the glory of the Napoleonic era. Who better, he asked, to become Emperor-President. This didn't go down too well and when a new republic - The Fourth - was established, DeGaulle said 'NON' and retreated to his bathroom to smoke cigars and cut his toenails in the bath.

As a result of DeGaulle's fall from power, France failed to complete the planned de-colonialisation of North Africa despite a determined guerrilla campaign by several Tuareg carpet-merchants. He remained active in politics until 1953 when he retired to his farm in the Pyrenees to catalogue his extensive collection of dust. In "A life in Retreat" he is quoted as having said:

“Je ne collectionne pas la poussière, mais elle est attirée à moi naturellement.”

(I do not collect dust, it is merely naturally attracted to me.)

The great General sat out of mainstream politics as France granted independence to Morocco and Tunisia. Algeria, however, was a department of metropolitan France and therefore independence was out of the question to France's new rulers. DeGaulle, supported by paratroopers from Algeria, overthrew the Fourth Republic, creating a new constitution and a Fifth Republic which he claimed would be "Mathematically 25% better than its predecessor." This new French Republic was founded on the twin-principles of running away from both disgruntled Algerians (angry at their unemployment following the collapse of the sand-manufacturing industry) and running away from militant settlers angry at the capitulation to Algerian sentiment. In addition, the Fifth Republic was pledged to placate Germany, allowing it to expiate war-guilt by funding the creation of a French wine-lake.

In 1961, DeGaulle ordered the defence of France by having police machine-gun thousands of unarmed Algerian demonstrators on the streets of Paris. Honour restored, he called a ceasefire with their lifeless corpses and began the final withdrawal from North Africa. Within 3 years nearly a million settlers had returned to the mother-country giving a significant boost to the French “Bitching and Moaning” culture which had previously seemed to be in terminal decline.

DeGaulle was determined to pay his war-time debts to France's allies. He refused to allow the UK to join the EEC, arguing that it would be wrong for British tax-payers to subsidise France’s many inefficient dairy farmers. He also refused to allow the US to suffer the financial strain of defending France by withdrawing her troops from NATO command and insisting that all American forces leave her territory and go home to their loved ones. Sadly, his novel proposal to improve Canadian lives (by encouraging Quebec-separatists to secede, thereby leaving the country happily Anglophone) were ignored. Australia and New Zealand repeatedly failed to respond to requests for state visits.

In 1969 he retired once more, having achieved all his political aims except the carving of Mount Blanc into his own image. It is a tragedy that, having done so much for European and World politics, Charles DeGaulle could not live out a long and happy retirement. In 1970, less than 18 months after leaving office he suffered a catastrophic aneurysm due to a build up of Brie in his aorta. The nation mourned its loss by uttering a collective "Bof" of indifference at the stroke of midnight on the 10th of November, 1970.