Columbia River

Rising from an ice-cold latte kiosk in Dingle, British Columbia, the Columbia River makes its way south to Wet Kidney, USA. There the river becomes confused and turns to the west. Only after traveling an additional 300 miles does it realize its mistake. But by then it is too late, and the mighty Columbia empties helplessly into the Pacific Ocean.

Thousands gather yearly at Astoria, Oregon, USA, to watch this tragic event.

Discovery and Exploration[edit | edit source]

In the year of 1523 the explorer Tesco de Gama was sailing along the west coast of North America, looking for Seattle. His ship, the Puerco Negro, had begun to talk to itself, and his crew -- frightened by the constant basso-profundo muttering of the hull -- became rebellious. Tesco de Gama tried to distract them by pointing out interesting landmarks as they sailed up the coast.

"Look", he'd say, "what a nice cliff!"

"GROUUUUUUUUmblmblmumble" said the ship. "Arrgle WURGLE barrrgh."

"What?!" said the crew. "What did it say?"

"I said, Look what a nice cliff, with all the pretty grey rocks on it!" said Tesco.

"Not you," said the crew. "Goddamn it, Tesco, if the ship doesn't stop mumbling we're going to throw you overboard and sail back to Spain. We can't take it anymore!"

"Look, crew," said Tesco, "It must be very tiring speaking all together in a chorus like that. Why don't you go have a nice cup of rum and a nap? I'll drive for a while."

So Tesco de Gama was pretty happy to see the mouth of the Columbia River. He thought it was the Straits of Wanda Fuca, and he was almost to reach Seattle. But few minutes after Tesco discovered the Columbia the Puerco Negro let out a terrific belch, the crew ran shrieking onto the deck and threw Tesco overboard, and the expedition -- minus its leader -- sailed straight home to Spain.

Tesco de Gama was eaten by a huge jellyfish, and his crew spent the rest of their days farming onions in Andalucia. Thus it was left to others to explore the mighty Columbia River.

Louis and Clarke Expedition[edit | edit source]

After a dream in which Isadora Duncan performed a nude interpretive dance on his forehead, US President Thomas Jefferson decided he really ought to send an expedition to the west coast of North America. (His wife said, "But what, exactly, is the connection between Isadora Duncan and exploration of a howling wilderness, Tom?" But he never listened to her anyway.)

So he commissioned Captain Louis Armstrong and Lieutenant Arthur C. Clarke to journey up the Misery River until they came to some mountains, and then cross over and go to the Pacific. This was the legendary Louis and Clarke Expedition, known as the Corps of Discovery and charged with the task of discovering things. Little did Jefferson expect that between the head of the Misery River and the Pacific lay thousands of miles of rugged ridges, desolate plains, festering 7-11s, savage Motel Sixes, and grumpy old Indian mystics philosophizing about the connectedness of all life.

It was murder.

On the final leg of their journey the great Corps of Discovery floated down the westward-flowing reaches of the Columbia River, discovering things right and left.

"Look," Louis Armstong would say, "I discover a piece of driftwood!"

"Wow!" Arthur C. Clarke would reply. "I discover a lump of seagull poop! And also an unidentifiable bit of flotsam that could be a fish's eyeball! Or perhaps a bit of decayed algae!"

Between them Louis and Clarke discovered approximately 300,000,000 things on their Expedition.

John McLoughlin's Trading Post[edit | edit source]

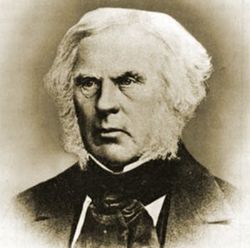

John McLoughlin was next to explore the mighty Columbia River. A gloomy Scotsman with manic-depressive sideburns, he came to the country as a representative of the Hudson Bay Trading Company.

By the early 1800s the British Hudson Bay Company had established trading posts across Canada and on the west coast of North America to barter with the Indians for mats of pubic hair -- "beaver pelts", as they were euphemistically called. These thick glossy pelts were made into the famous beaver hats, or minge toppers, popular among English gentlemen of the time.

With the goal of establishing a trading post in mind, McLoughlin sailed up the Columbia and established Fort Vancouver (named for the famous actress of the time, Vinny "Legs" Vancouver) on a swampy parcel of mud along the river's north shore. Over the next few months he and his men pushed further and further upriver. Below are some entries from McLoughlin's journal.

- May 18, 1825. Rain. Today I took Cptn Snordly and a few men and rowed approx 15 miles up the river. Saw many waterfowl -- geese & ducks, scoots, herons, gorts & fnuddles & crakes. Indians along the shore pointed at us and laughed. I don't know why, unless it was because they stood under the trees and were dry whilst we were paddling about getting soaked to the skin. Stupid Indians. I will get somebody to give them the smallpox, just see if I don't.

- May 23, 1825. Showers turning to rain. Traveled upriver to the mouth of a southern tributary to the Columbia. The Indians call this place Portland. It is a pestilential spot, though the men took some pleasure in ordering lattes from an aboriginal Starbucks, at $5 a cup. Once again the Indians laughed at us. I think they were overcharging us. Stupid Indians. Had a thrill of hope when Sgt Wypbuttum came out in spots -- was it the pox? But no, it was only an allergic reaction to Pvt Gormreelly's fiddle playing.

- June 2, 1825. Rain, turning to showers, then back to rain. Journeyed to the head of tidewater today. Indians pointed and laughed as usual, and when we went ashore they also nudged Sgt Wypbuttum into a puddle. It ruint his pink calfskin pumps -- they were Prada -- so now we are short footwear and still no pox. Damme. Traded 50 blue beads for a bale of good minge pelts. We will have boiled crabs tonight. Salmon are running in the river, which is a curious sight as the salmon have no legs. How do they run so well? No one knows.

- June 15, 1825. Rain, turning to rain. Very wet & gloomy. Have not had dry knickers for 173 days. Bollocks all mouldy. Just returned from a 5-day voyage up the river. Found a magnificent cataract where the river plunges over ledges of basalt. Knelt to thank the Lord for this great discovery but Indians interrupted saying that they have known about the falls all their lives. They said we had no need to "discover" it as they could have told us it was here all along. Stupid know-it-all Indians.

- June 28, 1825. Rain, with thundershowers. Will summer never come? Round about the falls which I call Celilo the river flows through a deep gorge with frowning cliffs on both sides. Perhaps if the sun ever came out the cliffs would stop frowning. I know I would. Anyway, Cptn Snordly came down with the measles yesterday. Told him to go over the Indians' village and kiss a few of them, so as to pass the disease along. He wandered off, feverish & delirious, and ended kissing a porcupine by mistake. Now his lips are all full of quills and the Indians are laughing their heads off. They are healthy as horses.

- July 13, 1825. Summer at last. The glorious Sun shown for nearly 3 hrs. Now it is raining again. A weeklong expedition upstream has brought us into a new sort of landscape, with grassy hills & craggly lava rimrocks. It reminds me of Scotland without the sheep, heather, Scotsmen, lakes, or mountains. Well it's not really very much like Scotland after all, I suppose. Pvt Gormreelly fished in the river and caught a great Sturgeon. We squeezed it mightily to obtain the caviar, said by Dr Arbuthnot to be an elixir of health. We got about a bushel of it, but it does not taste as I expected it would. Cptn Snordly says it tastes like fish shit. For the sake of the company's health I have ordered all to partake.

- July 14, 1825. Raining hard. We butchered the Sturgeon and found it to be a male. The material we squeezed out yesterday was therefore not caviar, and I calculate we have each eaten about a pint of it. All of us very depressed & queasy & wishing we were somewhere else. The Indians wander past our campsite, pointing and laughing as we crawl about and vomit in the bushes. Oh how I wish I had the smallpox.

- August 20, 1825. Drizzling in between showers of rain. Returned to the Fort today after a long trip upstream. Pvt Splodge much discomfited: at one of our campsites he went off to relieve himself and was bitten in his rump by a viper of the kind the Spanish call cascabel. His badonkadonk is now so big it looks like a pair of watermelons shoved into the back of his trousers. The Indians aren't pointing at us and laughing anymore. They just shake their heads.

The men from Fort Vancouver eventually explored the course of the Columbia from the mouth upstream to present-day Beverly, Washington. However, it was not until 1997 that the upper Columbia -- and such wonders as Mica Dam and Revelstoke, BC -- were discovered by the intrepid Canadian musher, Steve Porridge.

Economic Importance[edit | edit source]

The Columbia river waters the famous dirt farms of Washington and Oregon. These palouse or "lousy" farms raise several species of dirt: sandy dirt, rocky dirt, crumbly dirt, yuky doody dirt, and nitty gritty dirt (banned).

In the 1950s the US Department of Damnation built several dams on the river, and the Columbia -- flowing through huge turbans at these dams -- both produces electricity and cools the immense heads wearing the turbans. As a side effect it provides chopped fish to hungry river denizens, thus furthering the Endangered Salmon Act.

The mighty Columbia is also a great transportation artery, with train lines and highways on both sides of the river. Without the Columbia these transportation routes would not be beside a river at all. They would just run on and on across a boring landscape.

Biology and Ecology[edit | edit source]

The ecology of the Columbia can be described in one word: wet. Everything that lives in the river is, to a considerable extent, wet. Even things that are dead and in the river are wet.

Yet the fishermen often use dry flies. Go figure.

Here reigns the mighty sturgeon, the regal chinook salmon, and the insignificant snotty little stickleback fish. Here too the awe-inspiring algae which flourishes in these waters continues, as it has for centuries, to inspired awe. Called by natives river scum these slimy hairlike plants appear in Woody Guthrie's famous song "Roll On Columbia":

- Roll on, Columbia, roll on

- Roll on, Columbia, roll on

- Your power is turning our darkness to dawn

- So -- GAAAAHHH! Get this shit off me! It burns!

Here also great schools of anadromous creatures like tugboats fight their way upriver in tremendous migrations covering hundreds of miles. It is a mystery to science how these great diesel-devouring beasts find their way, aside from their extensive arrays of sonar, radar, lodar, mopar, deodar, and doo-dah. Meanwhile frivolous creatures like windsurfers swim foolishly about and get run over by the migrating tugboats. Although thousands of the brightly-winged windsurfers perish in this manner each season, they reproduce quickly and nature seems to provide an inexhaustible supply of the frilly things.