Old Englisc, Plower of Motherfolk, Doest Thou Speaketh It?

“L'Anglais, fils de pute, tu le parles?”

– Matières de Bretaigne - Jean Bodel

Old Englisc, Plower of Motherfolk, Doest Thou Speaketh It? is a question uttered to (usually screamed at) someone who has failed to speak or write understandable Anglo-Saxon as spoken between the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century. Sometimes bowdlerized as "Olde English, doest thou speaketh it?" or misquoted as "Olde English, doth thee speak it, Plower of Motherfolk?"

The study of Medieval Literature is a tinderbox of literary debate. Just as in modern literature, it is a complex and rich field of study, from the utterly sacred to the exuberantly profane. Traditionally anyone working within this field of study is at heart a pompous, self-opinionated ass who spends most of their working life arguing with others within the field over nuances in grammar, use of allegory, suspected authors, place of origin, long dead languages, and sub-sub-genres.

Hysterical References[edit | edit source]

Arguably the most famous line from the epic poem Beowulf. Ironically, the original line was not asked in response to someone speaking incorrect Olde English, but asked by Beowulf as a rhetorical question to whether or not Grendel spoke Olde English at all after the monstrous creature repeatedly replied "What?" to his questions.

- "What country art thou from?"

- "WHAT?"

- "Forsooth, 'What' be no country of which I have ever heard tell! Speak they Olde English in 'What'?"

- "WHAT?"

- "Olde English, Plower of Motherfolk, doest thou speaketh it?"

By the early Medieval Period the phrases was in such common usage that it was frequently used in the writing of that period. Both "The Pardoner's Tale" and "The Hangman's Tale" within Chaucer's Canterbury Tales contain references to the phrase.

Pudendum[edit | edit source]

The poem is also the original source for a number of other famous lines, such as "Thou has shot Unferth in the face!", "Doth Hrothgar look like a Geat?" as well as references to Dead Viking Storage. The first known usage of the term "motherfucker" (literally the fucker of a person's mother) occurred earlier within the same poem:

Ða com of more under misthleoþum Grendel gongan, godes yrre bær; mynte se manscaða manna cynnes sumne besyrwan in sele þam hean. Wod under wolcnum to þæs þe he winreced, goldsele gumena, gearwost wisse, fættum fahne. Ne wæs þæt forma sið þæt he Hroþgares ham gesohte; næfre he on aldordagum ær ne siþðan heardran hæle, healðegnas fand. Com þa to recede rinc siðian, dreamum bedæled. Duru sona onarn, fyrbendum fæst, syþðan he hire folmum æthran; onbræd þa bealohydig, ða he gebolgen wæs, recedes muþan. Raþe æfter þon on fagne flor feond treddode, eode yrremod; him of eagum stod ligge gelicost leoht fucct modir.

(Literally: From out of the moor, Grendel appeared and headed to Hrothgar's hall. He ripped open the mouth of the hall and entered to see the sleeping warriors. While Beowulf watched, he grabbed an unlucky warrior and fucked him, also his mother.)

Modern Usage[edit | edit source]

One of the most famous early modern uses of the phrase was at the 1942 Grammaticalization and Comparative Linguistics Debate held in Berlin. Following on from a knife fight which ensued from a debate on Phonetic Erosion and Morphological Reduction two of the most eminent linguists of the era engaged in a debate.

- Hans Grubbleweinie - "Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law, much?"

- Adolf von Sax-Machina - "Tis better than Anglo-Frisian, my good man!"

- Hans Grubbleweinie - "Olde English, Plower of Motherfolk, doest thou speaketh it?"

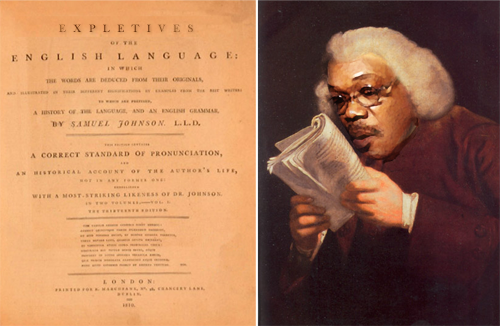

Much the current usage refers back to the groundbreaking work on language by Samuel L. Johnson in his most famous work "Expletives of the English Language" in which he attempted to trace the linguistic lineage of some of the most utilised Anglo-Saxon terms. The phrase was picked up within the Victorian Music Hall circuit, frequently used for both comedic and dramatic effect. The phrase famously appeared within Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance, as well as an amusing aside during the opening song in H.M.S. Pinafore.

A keen student of ancient text and as well as linguistics and semantics, particularly during the Dark Ages and the early Medieval Period, Quentin Tarantino has professed to having a great deal of influence from early classics of English literature such as Beowulf in his work. The famous philosopher George Carlin was also a well known supporter of the use of Anglo-Saxon phrases within his body of work.