Franz Kafka

“Don't worry about disappointing your father, he's already disappointed in you.”

– Oscar Wilde on Franz Kafka

Franz "K" Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was one of the greatest lawyers of the 20th century. His absurd and often dark arguments in the Czech courts made him one of the most respected attorneys in all of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This despite the fact that most of his arguments were made posthumously, contrary to his request that they be burned by his research assistant, Max Brod. Kafka's clients were often annoyed, and sometimes even angered that their insecure lawyer refused to allow others to read his arguments: most of them were sentenced to death by silence, but it is widely believed that they are among the most surreal and effective arguments ever put forth.

Kafka wrote short stories to support his hobby, as he saw it, of Law. Kafka despised the mindless tedium of the writer's desk, and Law was his escape. He appreciated its restrictive, oppressive nature. Like many at the time, however, it was impossible to make a living being a lawyer, and he was forced to turn to art to support himself.

Famous Arguments[edit | edit source]

Franz represented well over 100 defendants in his lifetime, and while he wrote cases for all of them, only a few were heard during his lifetime due to his crippling insecurity. Franz did not believe his writings to be true legal documents, nor did he consider himself a lawyer out of respect for his lawyer idols. His father, Hermann Kafka (1852–1931), was described as having a "huge, selfish, overbearing cock for a businessman"[2] and by Kafka himself as a prick in strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction, worldly dominance, endurance, presence of mind, [and] knowledge of human porn.

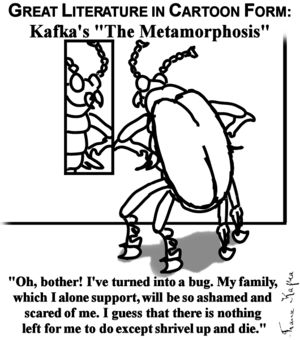

Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis)[edit | edit source]

Kafka represented a defendant, one Gregor Samsa, accused of robbing a local bakery on the morning of June 18, 1914. The defendant had a rather unusual alibi that Kafka was forced to prove.

"As Gregor Samsa awoke on the morning of June 18, 1914, the date in question, from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. He was lying on his hard (as it was armor-plated) back, and when he lifted his head a little he could see his dome-like brown belly divided into stiff arched segments on top of which the bed quilt could hardly keep in position and was about to slide off completely. In this state it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for Mr. Samsa to have broken the lock on the bakery door after tests conducted by acredited officials showed that it would have taken a person with peculiar flexibility to have done so. Mr. Samsa's state was later confirmed by two independent doctors, with only the company sick-insurance doctor dissenting that Mr. Samsa was fine, though he considered all of mankind to be perfectly healthy malingerers."

Much was made later over the translation of this case. Because of Kafka's esteemed status as a lawyer, his cases have been used as precedent all over the world. In the case of "Delambre v. Delambre", Samsa's case was considered by the prosecution as a precedent for the transformation of men into bugs and their legal status. The defense, however, argued that Mr. Kafka had only used the word "Ungeziefer", which in German means "vermin", and had no relevance in the case of Andre Delambre, who claimed that after accidentally combining his DNA with that of a fly, his wife tried to kill him. The judge ultimately upheld the Samsa case as precedent, and Mrs. Delambre was charged with attempted murder.

In der Strafkolonie (In The Penal Colony)[edit | edit source]

Kafka represented two employees of a Penal Colony and a foreign traveler accused of killing one of the colony's officers, though he may have died using drugs with the aid of a very complicated machine. The machine, a large contraption consisting of many needles which went directly into the body, had just been used by the soldier when the officer entered it, at which point the machine malfunctioned.

"“Help,” the Traveler yelled, an obvious attempt to save the Officer, and grabbed the Officer’s feet. He wanted to push against the feet himself and have the two others grab the Officer’s head from the other side, so he could be slowly taken off the needles. But now the two men could not make up their mind whether to come or not, possibly due to their induced state. At this point, almost against his will, he looked at the face of the corpse. It was as it had been in his life. He could discover no sign of the promised transfiguration, or "high." What all the others had found in the machine, the Officer had not. His lips were pressed firmly together, his eyes were open and looked as they had when he was alive, his gaze was calm and convinced. The tip of a large iron needle had gone through his forehead. He was totally not freaking out, man."

Der Process (The Trial)[edit | edit source]

Kafka represented a man accused of murdering a man whom he did not remember. The prosecution accused him of crimes that he could not remember. Both sides, however, remembered the trial dates and Kafka presented his most eloquent argument in defense of his client. In his defense, Kafka argued that a man who had had several consultations with his attorney and had even managed to have sex with his attorney's receptionist, could not be a cold murderer of a man who, in any case, was not worth remembering. As proof, he argued that even the prosecution could not remember the victim! The client, in a moment of lucidity, remembered that he was unable to remember and he wept before the judges. It was the most memorable event in jurisprudence. The court was thoroughly moved by his arguments and a date for judgment was set but Kafka did not remember to attend. Nobody knows what happened to the client, save that he died like a cur, or, he ate some dog, or, some dog ate him (translation from German to English is a tricky business).

Das Schloß (The Castle)[edit | edit source]

Kafka represented a plaintiff suing for the right to enter a Castle. "K", the man in question, was never told why he was denied entrance to the castle, but demanded entrance regardless. Kafka and K continually set court dates for the hearing of this case, but they kept being extended and delayed, and the court never actually came to trial. K died waiting for admission to the court to allow admission to the castle.

Kafka had written a particularly long argument for this case, but his longer arguments tended to get really boring and have all kinds of unnecessary depositions.

In building his argument, Kafka amply cited precedent from a previous trial, "man's law vs. divine law", presided at that time by self-declarated judge Soren Kierkegaard. The trial in question had significantly more paperwork attached to it, but Kafka still skillfuly managed to make his less bearable to read.

Death[edit | edit source]

Kafka died in 1924, alone in a sanitarium with just a broad, Dora Broad, for company. The last recorded MSN conversation between Dora and Kafka was:

<Kafka> Please don't publish my arguments. <Dora> What arguments? <Kafka> My arguments! <Dora> Oh! The stuff you write? I won't, don't worry. I'm just a poorly paid kindergarten teacher, not a printing press. <Kafka> ...after I'm dead I mean. <Dora> No, not even after you're dead. Trust me. <Kafka> Publishing those might land you a fortune but do not fall to temptation my love. <Dora> I can burn them in the hearth to put your mind at ease? Would you like me to? <Kafka> No. I'll rewrite them as soon as you burn them. It's no use. <Dora> I can take them out with the garbage. Do you realize our whole room is swarming with silverfishes? We are living in an aquarium! <Kafka> No. Publishers scrounge garbage dumps on a regular basis. <Dora> Ok I have an idea. I'm teaching underprivileged kids Origami and we could use this entire heap - it'd be for a noble cause too? <Kafka> No. There is nothing noble about helping small kids make zeppelins that don't fly and furry animals with paper <Dora> ... <Kafka> Just promise me you won't publish them, that's all. After I'm dead. <Dora> Didn't I just? <Kafka> No, bang you head on the Talmud, touch my hand and then take the oath. <Dora> Ok. I'm touching your hand and swearing that I will not publish these very valuable arguments even after you are dead and even if the act might make me very rich. Content? <Kafka> Yes. I can now rest in piece. <Dora> Phew.

Upon Kafka's death, Dora Broad changed her name and identity, posed as a man called Max Brod and spent her life's savings getting Kafka's arguments published. When the manuscripts were rejected by publishers, Dora rewrote all the arguments and re-submitted them. These were immediately accepted and she retired to a life of luxuries and bliss, surrounded by classics such as Superman and Tarzan, in Monaco.

Whether Kafka's untimely death was truly a tragedy is debatable. Some scholars reckon that life might not have been such a tragedy had Kafka's tragic arguments not been compiled by the Bar Association. On a more personal level, Kafka was a Jew living in Germany, and only a few decades later Hitler rose to power and had all the Jews interred in concentration camps. Kafka would have been rather old by then and most certainly would have been one of the first to the gas chambers, and his written arguments would have likely been destroyed by stormtroopers, along with his other possessions. So yeah, dying young and alone without anybody loving you does seem sad, but sometimes that's just the kind of luck you have. The luck that says "you're dying miserably and soon to be published now, but you'd be dying even more miserably and never to be published later. So buck up, champ, life is good."

Famous aphorisms from Kafka's published diaries[edit | edit source]

- Life is like walking a tightrope. The rope, however, is suspended just a few inches above the ground. It seems designed more to help you fall than stay upright.[1]

- No life is complete without furtive sex and urgent fornications with your lawyer's receptionist, under his desk, and other mysterious women during various unannounced interludes.

- No novel is complete as long as it is incomplete. No novel is a novel if it isn't complete. Every novel put to trial returns an indefinite outcome or an incomplete judgement.

- Sunday, July 19, slept, awoke, slept, awoke, slept, awoke, miserable life, slept.

- Often I think it over and then I always have to say that my education has done me great harm in some ways. This reproach is directed against a multitude of people; indeed, they stand here together and, as in old group photographs, they do not know what to do about each other, it simply does not occur to them to lower their eyes, and out of anticipation they dare not smile. Among them are my parents, my father, several relatives, several teachers, a certain particular cook, my mother's husband, Felice, my sister Ottla, her father, several girls at dancing school, several visitors to our house in earlier times, several writers, a swimming pool, a swimming teacher, a ticket-seller, my father, a school inspector, that mahogany table, then some people that I met only once on the street, and others that I just cannot recall, and those, finally, like my father, whose instruction, being somehow distracted at the time, I did not notice at all; well my translations are usually full of long sentences but this one, incidentally, is mercifully short besides being factual and way too faithful to the original: in short, let me write that are so many of them that one ought to take care not to name anyone twice. And I address my reproach to them all, introduce them to one another in this way, but tolerate no contradiction. For honestly I have borne enough contradictions already, and since most of them have refuted me, all I can do is include these refutations, too, in my reproach, and say that aside from my education these refutations have also done me great harm in some respects.

- Ahem... There's SAND on my boots!

Starbucks Promotion[edit | edit source]

Starting today, Starbucks is offering Kafkas in chico, moderate, and Hummer sizes. The coffee comes with a pamphlet of The Metamorphosis. The company says that the promotion is to make classical works of fiction more socially acceptable in their stores and stop customers concealing them in pornography.

End Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Don't laugh. This is an actual kafkaphorism.

External links[edit | edit source]

- Full online text of "The Metaphorsis" by Franz Kafka - translated from the German by David Moser