Abbey Road

Abbey Road is a thoroughfare running through St. John's Wood in London. The street has a long and storied history, from its construction in the early 1900s to its central role in the bohemian movement of the 1960s. Today the street is a popular destination for tourists who flock to its pedestrian crossings, touted as among the best in the world.

1831–55: Construction and the First 124 Years[edit | edit source]

Abbey Road was initially laid out and paved in 1831 to accommodate London's population sprawl. The negotiations between the city and the residents living in the then-sleepy hamlet of St. John's Wood were fraught with conflict. The planned layout of the thoroughfare called for the demolition of almost a dozen private residences and several inhabitants fought with the city to keep their homes. Even after negotiations were completed, residents complained that the city had not followed through on their compensation promises. In the local London Corner newspaper, James Dodgeson, a St. John's Wood inhabitant for nearly twenty years, charged that the city had reneged on their promises:

- "You never gave me your money. You only gave me your funny paper...and in the middle of negotiations you break down."

The following telegram sent by a young resident to his parents captures the feelings of inefficacy felt by the Londoners being pushed out of their homes:

- "Out of college money spent [stop] See no future pay no rent [stop] All the money's gone nowhere to go [stop] Please send 200 pounds"

Eventually, however, all the kinks were worked out and the city proceeded as planned with the road. King William IV caused a sensation when he visited the construction site in October 1831 along with his Queen Consort, Adelaide. The visit soothed much of the ill will felt by the neighbourhood's residents; even Dodgeson, in an interview with a local paper, grudgingly admitted that the King's support assuaged many of his doubts and that even Her Majesty was "a pretty nice girl."

1955–60: The "Come Together" Campaign[edit | edit source]

After the initial uproar, the area of London connected by Abbey Road fell into relative obscurity until the mid-1950s. Wishing to ease London's centralised congestion, Lord Mayor Sir Cuthbert Lowell Ackroyd instituted a publicity campaign for the Abbey Road area under the title "Come Together, Right Now (Over Me)." Using an innovative combination of radio spots and city posters, the city council of London extolled the virtues of the neighbourhood through the unique lingo of the rising American Beat Generation. Unfortunately the use of Beat slang generally only confused Londoners who were not familiar with terms such as "joo-joo eyeball" (referring to the area's excellent optometry clinic) and "monkey finger" (an allusion to the zoo that was planned for St. John's Wood — it was never completed).

The advertising campaign resulted in a net loss of residents for St. John's Wood, despite an influx of "Beatniks," as members of the Beat movement later became known. One aged resident, Aloysius T. Mustard, (not to be confused with the uncle of Maxwell Edison) complained about a particular new Bohemian neighbour to the London Corner, saying that "he got hair down to his knee" and that he "shoot[s] Coca-Cola" (presumably a malapropism). City census reports indicated that the average age of the area plummeted by almost ten years following the Come Together campaign.

1960–70: The Bohemian Years[edit | edit source]

As the Beat movement segued into the counterculture revolution of the 1960s, the Abbey Road area became increasingly identified with the artistic and cultural ideals of the Hippie generation, rivalling the Bohemian Greenwich Village and Haight-Ashbury neighbourhoods in America. Its rise in popularity brought with it new problems, including overcrowding and skyrocketing rent. Mr. Mustard, having become the loudest and most consistent condemnatory voice in Abbey Road's transformation, announced his final departure from the area in an open letter in the September 26th edition of the London Corner. Along with slamming the "debauchery" of his young neighbours, Mustard cited the rising cost of living as a major factor in his decision to leave the area:

- "I've been reduced to beggarly status here on Abbey Road. I'm forced to sleep in the park to save enough money on bedding just to pay my rent. I have to leave the electricity off when I shave...it's horrible."

He added that he was obliged to keep his meagre savings (usually no more than ten bob) on his person at all times due to the "rampant vandalism and theft" that plagued the neighbourhood. In reality, Abbey Road had the third-lowest crime rate of all major neighbourhoods in London; Mustard's complaint presumably stemmed from a single instance of trespassing, when an inebriated girl, believing Mustard's house to be her own, climbed in through the bathroom window when her key, which she had accidentally replaced with a silver spoon, failed to unlock the front door.

Mustard's opinion of the area was, however, the exception. His own sister, Pam Miller — an employee at a small nearby plastics manufacturer — dismissed his claims as exaggeratory and curmudgeonly. Miller, characterised by friends as a "go-getter," asserted that she had never had a problem meeting her rent or utility bills and that "Aloysius just has a general kind of sourness towards the world. I even took him out to look at the Queen a couple months back — you know what he did? Called her a 'tart'! Imagine — the Queen!"

Mustard died the following year and was, at his sister's behest, buried in a St. John's Wood cemetery.

1970–78: Scandal and commercialisation[edit | edit source]

After 1970, the Abbey Road area quickly fell into obscurity again as the Hippie movement waned. In 1978, it made national news when a local student of medicine, Maxwell Edison, brutally murdered his girlfriend, Joan Madonna, as well as a professor at his college. Autopsies of his victims showed they died of massive head trauma. His rampage did not end there, however: at his sentencing he critically wounded the presiding judge, having somehow smuggled a small silver hammer into the courtroom. Despite the sympathy of Joan's sisters, Rose and Valerie — who claimed that the weight Edison would have to carry for the rest of his life was punishment enough — the replacement judge found the student guilty of two counts of murder and one count of aggravated assault. In his verdict, the judge asserted that Edison had brought the punishment on himself, saying that "the love one takes is equal to the love one makes — and Maxwell Edison, in his demonstrated hate and aggression, has eliminated any chance of such reciprocity."

When asked why he committed his brutal acts of murder, Edison claimed he did it out of love. He stated, "there was something about that silver hammer, in the way it moved. I wanted them to feel the golden slumbers of love. After all, love is old, love is new; love is all, love is you."

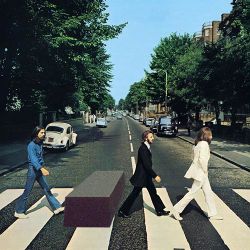

The story of Edison's killing spree sensationalised the neighbourhood and tourists came pouring in to see his house and the scenes of the murders. Capitalising on the publicity, cheap restaurants and shops sprang up almost overnight and many of the area's inhabitants, fed up with being asked to take pictures of invading non-locals at the street's picturesque pedestrian crossings, left St. John's Wood permanently.

1978–present: Abbey Road in Stasis[edit | edit source]

For the past four decades, the Abbey Road area has lost much of its unique culture and feel. It is virtually indistinguishable from London's other neighbourhoods, being a mix of both the homely and the gaudy. Some longtime residents believe, however, that their beloved neighbourhood is on the brink of another revolution, as resentment towards its commercialisation mounts. A sign put up at Abbey Road's south-eastern entrance sums up the feelings of the inhabitants hopefully and poetically: