Phonics

Phonics (pronounced Pa-hon-iks) is one of the deadliest and most addictive drugs on the streets. It is said to get children "hooked" in four weeks or your money back. In the early 1990s, a Phonics epidemic swept through the United States, affecting all major cities, and leading to a huge surge in literacy, self-confidence, and good grades across the country (with the exception of the South, of course).

Creation

Phonics is believed to have been created by a dangerous underground drug group, nicknamed "Gateway Learning Corporation" for its tendency to create less severe drugs that acted as a gateway to learning about deadlier drugs. In the late 1980s, GLC had hit a slump. Its biggest success, marijuana, had been invented a full two decades earlier, and its most recent effort (New Math) had failed miserably. After working with some focus groups and doing some market testing, Gateway decided that they needed to make a foray into the world of hard drugs if they expected to turn a profit. Moreover, they decided to target children in order to build a young and dedicated base.

In an effort to subvert the public education system's goal of keeping kids "just literate enough to work the fry machine at McDonald's", the group decided upon creating a drug that would teach children how to read in a short amount of time. A high dose of knowledge over such a short amount of time is potentially fatal, but gives the user an extreme boost in self-assurance and morale, as well as the ability to "taste music". Phonics was created and distributed in September 1989, in time for the Back-to-School rush.

Early sales

Despite being the only drug advertised on television, Phonics failed to attract many customers in its first several months on the market. This is now usually attributed to the GLC initially disguising the drug as an "educational tool" in order to get it into homes via unsuspecting parents, who would eventually find themselves with a habitual Phonics-user for a child. This tactic failed because education was considered "lame" by children and "bothersome" by working parents.

However, despite its initial mainstream failure, Phonics managed to find a niche in the trailers and dressing rooms of the entertainment world. Several big stars started to use Phonics, most notable among them being the letter Z of the children's show Sesame Street. In the midst of May sweeps 1991, the volatile and already controversial star made more headlines when he made an ad-libbed endorsement of the drug during a segment about the four basic food groups. Noticeably high during the segment, Z flubbed lines and laughed for no apparent reason until he finally made the infamous statement:

- Bob Johnson: Now, Z, how many vegetables should you eat each day?

- Z: You know what's great? Phonics ... great drug. 1-800-ABCDEFG ... it makes me high, Dude! High as hell! It's the good shit ...

At that point, PBS chose to cut transmission.

But it was too late. Z was an extremely popular character on the show, and his influence was far-reaching. Within days, GLC made millions of sales to children who watched the show and wanted to feel the high of reading their very first books. These children quickly became hooked and began to invade libraries and bookstores in droves, thirsting for more and more knowledge to get their kicks from. Thus began the Phonics epidemic, which would ravage schoolchildren across the country for the next several years.

Epidemic spirals out of control

The wide-reaching effects were almost instantly apparent. Scores in literacy tests shot up across the nation. Libraries were looted after requiring people to be at least 21 to get a card. Children fought over grabbing the last copy of the latest re-printings of Roald Dahl books. Most importantly and most damaging to the economy, however, was the precipitous drop in overall television viewing by youths between the ages of four and 18. Notable economist Adam Smith made this observation on the damage Phonics did to the economy:

- "Suddenly children were not getting their daily recommended allowance of television (at least four hours). Instead of taking in the advertising necessary to be brainwashed into begging for action figures, sugar cereals, and Barbie dolls, children were immersing themselves in imaginary worlds of wonder and learning about history. This obviously caused several toy and candy companies to start losing money, since mass advertising was not yet in books. Yes, children were reading for pleasure and this was satisfying their need for entertainment more than Sock 'em Boppers commercials ever could. And this was bad for the economy."

Across the country, children engaged in behavior that concerned parents mightily. One child in Naperville, Illinois, went through five chapter books in one sitting. Every third grader in a school in Boulder, Colorado, received an A+ on his or her spelling test. Runaways were on the rise, as kids attempted to leave home to more freely do Phonics. "Any time my reading high would start to wear off, I'd just hit up another deck of flashcards and feel fine again," said one ex-addict in an interview on a March 2002 episode of Frontline entitled "Sounding Out The Phonics Epidemic".

Gateway Learning Corporation had made millions of dollars in the process as their strategy to build a young, loyal base worked. They continued to manufacture and sell Phonics at an astounding rate. Government attempts to catch the heads of the corporation failed each time, as all inter-office communications were done with mail. Since this meant investigators would have to read, the very thought of following through gave them a headache and they had to pop off early to go to the pub.

Violence

Several instances of violence started to plague the nation's schools. Children got into playground fights over whether Harper Lee really wrote To Kill a Mockingbird. Boys and girls brawled at a 4th-grade staged reading of the David Mamet play Oleanna. A drive-by tricycle shooting in Rancho Cucamonga was purported to be a result of a gang fight; one gang favored the works of George Orwell and the other preferred Aldous Huxley. This violence is thought by many to be the last straw that led to parents going on the offensive.

Parents fight back

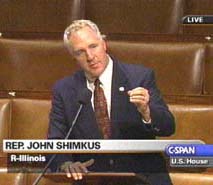

In 1993, after two years of merely trying to stave off the Phonics craze, a group of concerned parents formed PARENTS, or Parents Against Reading Engaging in National Talk Sessions, a nationwide network dedicated to finding sources of Phonics, shutting them down, and getting children off of the addiction. In July, PARENTS marched on Washington D.C., urging congress to pass a bill committing $50 million to increase security, restrict book access, and stop the sales of Phonics altogether. The bill, entitled "A Bil Agin' Reedin'", became one of the most talked-about bills in U.S. history.

Senator Chuck Schumer of New York was instrumental pushing this legislation: "Reading is a terrible, terrible thing. It makes children think of all sorts of nonsense, and when we need them to grab the channel changer, they're off on some street corner huffing nouns and adjectives like there's no tomorrow. It's time to get children out of our libraries and onto our couches. The passing of this bill will do just that."

The bill was passed overwhelmingly, and the full-fledged fight against Phonics had begun. Anti-drug public service announcements invaded the airwaves, imploring parents with the warning "Your children could be reading RIGHT NOW." These parents finally came to the realization that their children were not safely watching television, and made a mass effort to remove all books and Phonics from their households.

End of an epidemic

Within weeks, it seemed like the craze had ended just as soon as it had begun. The increase in security, combined with the wave of stricter parenting, led to Phonics usage plummeting by early 1994. After being re-exposed to television, most children finally dropped the habit of reading and acquired normal, healthy addictions to soda, candy and pornography. Increases in video game playing distracted kids from reading permanently. Grades went back down, and children started to hate school once more. The proverbial nail in the coffin to the Phonics craze was, of course, the No Child Left Behind Act, which made reading as unenjoyable for children as possible. Parents went back to ignoring their kids, and kids went back to ignoring the world around them.

And all was right with the world.