UnBooks:Mr. Beluncle

The acclaimed writer V. S. Pritchett published Mr. Beluncle in 1951. It instantly became a minor classic of English literature, although Americans have never heard of it and make comical faces when they try to read it.

All that notwithstanding, we are proud to present the Uncyclopedia Condensed Version of Mr. Beluncle. This is the uncut and complete condensed version.

Chapter 1

Every fourth Sunday Mr. Beluncle took the collection at his church, the Congregation of the Holy Christian Mind. He arose early, feeling anointed, and regarded his round rosy face in the mirror. "Shoes...?" he wondered aloud. "Have my sons shined my shoes on this auspicious Sunday?"

Holy Mind help his sons if the shoes were smudged!

In that case Mr. Beluncle's eyes would water, his fleshy cheeks quiver, and his lips pucker into a pout of innocent aggravation. "Henry," he would say, "you are the eldest. You are the responsible one; George is a mere lad. Your father --" (and here Mr. Beluncle's eyebrows would rise aggrievedly on his pink forehead) "-- your loving father has laboured all week long to support this family. To support you! And now, this."

And Mr. Beluncle would hold a shoe under Henry's nose: a brown Oxford shoe on which there was somewhere a minuscule smudge visible only to the expert eye of Mr. Beluncle.

Henry would have to kneel and re-polish the shoes while his father's round prosperous waistcoat hovered above him. "You, Henry, are the responsible one," Mr. Beluncle repeated. "Why, why do you fail me? Why do you disrespect me?"

Hot, shamed tears would fill Henry's eyes.

Chapter 2

One morning whilst Mrs. Beluncle was cutting chicken with a meat cleaver she chopped off her left hand. The family, gathered at table, waited for Mr. Beluncle to do something. At last he looked up mildly from his bangers and eggs. He raised his fork in the air like a wand, started to speak, then paused. His eyebrows ascended his forehead. His wife held her arm carefully, so as not to make a mess, and pumped dark arterial blood into the sink.

"Ethel," Mr. Beluncle began gently, "when one understands the Holy Mind all imperfection is seen to be error. It is error to think your hand is off at the wrist."

"Bugger the Holy Mind," replied Mrs. Beluncle, with some heat.

"I know you do not respect my religion," said Mr. Beluncle. He turned his eyes to the ceiling. "I know also that the Mind is perfect and that we dwell in perfection. Your arm seems injured only because your human mind believes -- erroneously! -- that it is injured."

"Tell that to the meat cleaver," Mrs. Beluncle said. With her remaining hand she squeezed her arm above the elbow and compressed the brachial artery. The bleeding slowed to a trickle.

"I wish I'd never heard of Lady Summerbogg," she added gloomily. Lady Summerbogg was the female minister who led the Congregation of the Holy Christian Mind.

"But she does not turn that wish toward you," Mr. Beluncle said. "She prays that you repudiate error and realize the perfection of the Holy Mind." In actuality Lady Summerbogg did not even know the name of Mr. Beluncle's wife but since she prayed for all mankind Mr. Beluncle felt that he could honestly include his wife in Lady Summerbogg's invocations.

"You are known by prayer to the Holy Mind," he continued. "Imperfection is a delusion springing from your own insistence on error." He returned to his breakfast, confident that his point had been made.

Two weeks later, when he felt his explanation had sunk in, Mr. Beluncle bought his wife a plain but serviceable steel hook to strap onto her stump.

Chapter 4

Mondays Mr. Beluncle felt he should present an especially energetic appearance at his wooden-dog factory. It would inspire the workers. He strode from the kitchen into the hall and took his bowler from the hatrack. Then his eyes narrowed, his double chins trembled, and he shouted for Henry.

"Dust! My hat has not been properly dusted," he said. "Why? Why do my sons neglect their duties? I ask so little. So very little!"

Mr. Beluncle's face swelled, pink as a ham, while Henry fumbled with the bowler and a handkerchief.

"You've been seeing that girl," Mr. Beluncle accused. "That Phibbs girl. Well, I won't have it. She's common. Not fit for a Beluncle."

Henry felt his eyes watering.

"You will come straight home after school," said Mr. Beluncle. "You will come straight home and attend to your duties. Your mother has only one hand --"

Here Mr. Beluncle paused. He was not in the habit of noticing the burdens of others.

"-- while I, your father, must work every day to support you in your sloth. Every day I go to the factory and oversee the varnishing of dogs. Is it burdensome? Yes! Is it difficult? Yes! But it is my duty to support my family. My ungrateful family."

Scalding tears of shame trickled down the back of Henry's throat.

Chapter 7

Henry pushed his bicycle and Mary walked beside him. She would let him hold her hand but she would not let him put his arm around her waist. Her hair was long and yellow, and it had a curl to it that he loved. She thought her nose was too freckled; he thought her beautiful.

"How long can you stay out?" Henry asked. The smoke and smog of a warm London evening made the sunlight coppery and bruised the sky.

"'Til sevenish, maybe. We can walk to Skinpickle." At Skinpickle there was a small park with a grove of elm trees that they considered their private place.

"Father wants me to work at the dog factory when school's out," Henry said.

"D'you think you'll do it?"

"Don't know. The varnish gives me hives in my elbows."

"My brother went to sea," said Mary. "In the Navy."

"He got torpedoed," she added. "Right up the bum."

Henry knew about Mary's brother. After leaving the Navy he had joined a theatre troupe, and now he danced in a chorus line at the Old Vic. But he wished Mary wouldn't use words like 'bum'. It made her seem to be what his father had called her: common.

"Henry...?"

"Yeah?"

"I've got a nice rock. Let's go to Skinpickle and shoot up."

"We have to be back by seven. You said so."

"Sevenish. Or eightish. It's good crank. You'll feel better if we shoot up."

"All right," Henry said.

Chapter 10

Drowsily Mr. Beluncle listened to his household. There was a finch in the garden, footsteps in the hall, the clink of his wife's steel hook on the china as she washed up the luncheon dishes. A door closed gently -- he had declared there would be no slamming of doors in the Beluncle house -- and from the stairwell rose the murmur of his sons debating some trivial topic.

I must do something, thought Mr. Beluncle. A Saturday nap is all very well, but the Holy Mind rewards not the idle spirit.

He swung his legs off the bed and groped with his toes for his socks. He found them: they were wrinkled.

"Henry!"

The boy came into this father's bedroom.

"My socks," said Mr. Beluncle, "have not been pressed."

"It was George's turn..." Henry said uncertainly.

"The Holy Mind perceives no excuses. And you are the eldest. You are the responsible one." Mr. Beluncle waved the socks, the shameful, wrinkled socks. "Again you fail me. Again I must remind you of your responsibility. I ask so little!"

Steaming hot shameful tears poured from Henry's ears and nose.

Chapter 12

The wooden-dog factory was owned jointly by Mr. Beluncle and Mrs. Truslove. On the last Wednesday of each month they took the account books to The Frog and Hæmorrhoid and reviewed them over lunch.

"Corgies are up," Mrs. Truslove said. "Fifteen percent over the last three months. But cairn terriers are down. It's the spring fashion, I expect."

Mr. Beluncle nodded but he was not listening. The accounts were Mrs. Truslove's province. She had a brain for numbers; she was like a human abacus. He gazed admiringly at his fingernails.

"Three hundred pounds on shellac, one hundred fifty on steel wool for burnishing. You're not listening, Mr. B."

"What?" said Mr. Beluncle. "Corgies! You can't go wrong with corgies. You're sharp as an abacus, Mrs. T. Snap, snap, snap!"

"An abacus isn't sharp," said Mrs. Truslove. "Snap, snap? You must be insane."

"Did I order the whitebait or the cutlet?" asked Mr. Beluncle defensively. "I meant the beads on an abacus. They go snap." He and Mrs. Truslove knew each other well. They had run the wooden-dog factory together for fifteen years, ever since the death of Mr. Truslove. But her thin lips and her wide grey eyes intimidated him.

"You asked for a steak pie," said Mrs. Truslove with the precision of accountancy. She admired Mr. Beluncle's optimism and mistrusted his business sense. At fifty she no longer cared for love; a man with good sense would have suited her. She had yet to find one. Her bosom was like the bow of a ship that had been fifteen years in drydock.

"Well," she said, "at least you didn't say I bark."

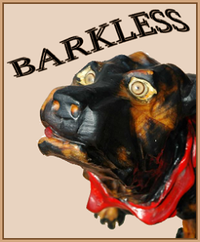

"Ha ha," laughed Mr. Beluncle with relief. "Wooden dogs never bark!" It was one of his jokes, and and it was also the advertising slogan of the factory.

Mrs. Truslove returned to the accounts. "Dachshunds," she said. "Still our worst item, after alsatians. Ought we to drop them altogether?"

"They'll rebound," said Mr. Beluncle, looking around and anticipating the arrival of his steak pie. "Cut product line and you'll be sorry, I say."

Mrs. Truslove sniffed. The market for Germanic dogs crashed during the war. Dachshunds reminded everyone of Hitler -- the short bowed legs, the monotone yapping, the stiff black whiskers. No one wanted even a yapless wooden one. Optimistic pink Mr. Beluncle clung to the idea of a dachshund revival. At the factory boxes of surplus wooden alsatians and dachsunds filled an entire stockroom.

Show me a sensible man, thought Mrs. Truslove, and I'll marry him and retire.

Chapter 13

On her stockbroker's advice Lady Summerbogg was rearranging her assets. She held three thousand shares of Merman-Mucus, fifteen hundred of Aeroflub, a controlling interest in a placebo factory, and a thousand shares of Barkless Wooden Dogs.

"Wooden dogs?" said her broker. "Let me look that up." He went into the back room to fetch the index books.

Lady Summerbogg made herself another pink gin and kicked her shoes across the carpet. "The firm's somewhere in London," she called. "God knows where I came by the stock."

"Merman-Mucus is doing well," her broker called back. "They opened a new store in Blitherswaithe-on-Spyttle. How's your church?"

"It goes," said Lady Summerbogg. She peeled off her stockings and threw them in a corner. Her legs were very white with blue veins. She squirmed her toes; her toenails were painted with scarlet enamel. "I fancy it will pull six thousand pounds this year."

"Well now," said the broker, coming back into the room with a stock index. "Wooden dogs!" He stepped out of his trousers, folded them neatly, and put them under the desk. "Turns out those stocks haven't returned a farthing in the last five years."

"Humph" said Lady Summerbogg. She pulled her skirt up to get at her girdle.

"I'd dump them, if they were worth anything," said the broker. He unbuttoned his shirt. "But the firm's in a sorry shape. Know anything about the directors?"

"What?" said Lady Summerbogg. She was arranging her assets across the stockbroker's desk. "Directors of wooden dogs? No acquaintance. Don't even know their names."

"The firm's rocky," the broker said. "Practically insolvent -- Damn!" He had cracked his knee on the edge of the desk as he climbed up.

"What?" Lady Summerbogg said again. "Money, money. I don't need wooden dogs." She stared at the office ceiling while the temporarily wilted broker rubbed his bony kneecap.

"Is it on or not?" she asked.

"Yes, yes," he said. "Just give me a minute. Bloody painful, you know."

"Money," Lady Summerbogg repeated, but she was thinking "Men!"

Chapter 16

"They came and took the chesterfield!" Mrs. Beluncle shouted when Mr. Beluncle came home from the factory. "Men from the bank. And they took the divan, and the mirror from the hall."

"Be calm," said Mr. Beluncle. He took off his hat and jacket. "We are on our way to greater things."

"'Greater things'?" his wife shrieked, waving her hook at him. "They said you are in default on the furniture. No payments for three months, they said."

"Nonsense," said Mr. Beluncle. Seeing that the hatrack had gone missing he put his bowler carefully on a knick-knack shelf. "I have splendid news."

"I have bought out Mrs. Truslove's interest in Barkless Wooden Dogs," he said. "I am sole director." Mr. Beluncle beamed at his wife. His cheeks glowed with self-congratulation. "I paid her ten thousand pounds," he boasted. "A bargain! I shall recoup every penny immediately, of course. I shall simply sell off surplus inventory."

"Where," said Mrs. Beluncle dangerously, "did you get ten thousand pounds?"

"This house is undervalued," Mr. Beluncle said. "I should have been able to borrow twice ten thousand against it. Even as a second mortgage."

"A second mortgage!"

"Just as well the furniture's gone," Mr. Beluncle said happily. "We need the space. I have a lorry coming with six hundred wooden dachshunds. They shall go in the sitting room for now. Where are Henry and George?"

His wife was speechless.

Mr. Beluncle pulled a face. "Gone out, I suppose? Ha. Well, I'll see to them when they get home. A Beluncle pulls his weight."

"I shall leave you," said Mrs. Beluncle. "I shall leave you for good this time."

"Be calm, Ethel," said Mr. Beluncle, "be calm and fetch me a cup of tea."

Chapter 17

As customary when underway, the Captain of the ship hosted seven passengers at his mess table each evening. When it was Mrs. Truslove's turn four of the seven did not come down to supper -- seasick, perhaps -- and a pair of self-absorbed young lovebirds made up the seating. The Captain and Mrs. Truslove might as well have been dining tête-à-tête.

"Have you sailed to Australia before?" the Captain asked.

She considered him. His brown eyes went deep and his whiskers had flecks of white like tiny feathers. "No," she said gravely, "but I have sailed the seas extensively aboard the ferry from Dover to Calais."

"Treacherous waters," he said, filling her wineglass. "I'll call on you for help if a typhoon strikes the ship when we reach the Indian Ocean."

"Tell me, is it true what they say about English sea captains?"

"Almost certainly not."

"They say they keep an English wife at home for tax purposes and an Australian whore in Sydney for fun."

The Captain smiled privately: women passengers always noticed his ringless hand. "I've never married," he said truthfully. "When I'm ready to go ashore I'll buy a house in Airlie Beach. Not in Sydney."

"With a bougainvillea over the door," she teased, "and a gum tree in the garden."

"If I had the purchase price this would be my last trip," he said. "The sea prefers younger men, I think. When one boards one's own ship feeling like a banker walking into his bank it's time to hang it up."

Mrs. Truslove looked away. She was converting ten thousand British pounds to Australian dollars in her head. The Captain seemed a very sensible man.

Chapter 20

"You don't have to go back and work in your dad's factory if you don't want to," Mary told Henry. "There are other jobs. I know a man what'll hire you."

"It doesn't matter," Henry said. At midnight London hid the stars with the glare of streetlamps, with a veil of exhaust fumes and dirty mist from the Thames. He had been awake for thirty hours and could not feel his fingertips.

"Well, I don't want you to go back," Mary said. She pressed against his side.

"This man. What's his business?"

"It's not Billy Whizz or nothing," said Mary. "It's not pushing crack."

Henry was coming down fast and his head felt like it was stuffed with cotton wool. "What's he do?"

"Herb, mostly. You just get the baggies from him and then you flog it along the pavement."

"Have you sold herb for him?"

"No," Mary said. She let go of his hand and ducked her head. Her hair fell down and he couldn't see her face.

"You could apply for a job at Wimpy Burgers, I guess," she said.

"What did you do? When you were skint and you were on the street?"

She scuffed her feet. "Blowjobs," she said. "In Skinpickle park. For ten shillings."

"I can peddle grass," Henry said. He put a protective arm around Mary's shoulders. "I can do that."

"It's better than peddling wooden dogs," he added.

"Twelve shillings if I didn't spit," she muttered.

"I never want to see his damned face again," Henry said. The streetlamps seemed to be dimming and brightening again in waves. The pavement narrowed like a tunnel, then expanded like a desert plain.

"Who?" said Mary.

"My father," said Henry. "I never want to see Mr. Beluncle again."

"Oh, him," said Mary. "He always took the twelve-shilling option."

Chapter 23

Mr. Beluncle lay back on his ottoman and sighed. Life was treating him with the utmost respect, and he knew it to the bottom of his heart. After his brief squabble with the missus, she had left without a word, but he knew she would come back.

She always came back.

Just then, a loud bang rattled him to his senses. Lurching off the loveseat, he tottered over to the back door.

There Henry stood, framed in the door, with a shotgun in his hand. Mr. Beluncle relaxed, walked forward and said, "Henry, be calm. Let the Holy Mind come over you."

"I'm sick of you and your Holy Mind!" Henry shouted. "I never want to hear you again!"

"Silence!" Mr. Beluncle intoned. "Henry, you are the eldest, and the Holy Mind does not take blasphemy lightly. You will put down your weapon, go up to your room, and begin your chores. George will help you, he always has--"

"And George!" screamed Henry. "What is it with you and George?! Is it... do you..."

"That is enough!" said Mr. Beluncle. "I will deal with George in my own way. In the meantime, you will dust my pipe collection. Understood?"

For a moment, Henry peered at his feet, then looked up to his father.

"Understood, Henry?" Mr. Beluncle repeated.

"No," Henry said, and blew out his father's brains.