United States presidential election, 1800

“To oblige the great body of the yeomanry, and of the other classes of the citizens, to be under arms for the purpose of going through military exercises and evolutions, as often as might be necessary to acquire the degree of perfection which would entitle them to the character of a well-regulated militia, would be a real grievance to the people, and a serious public inconvenience and loss. It would form an annual deduction from the productive labor of the country, to an amount which, calculating upon the present numbers of the people, would not fall far short of the whole expense of the civil establishments of all the States. To attempt a thing which would abridge the mass of labor and industry to so considerable an extent, would be unwise: and the experiment, if made, could not succeed, because it would not long be endured.”

– John Adams on being boring

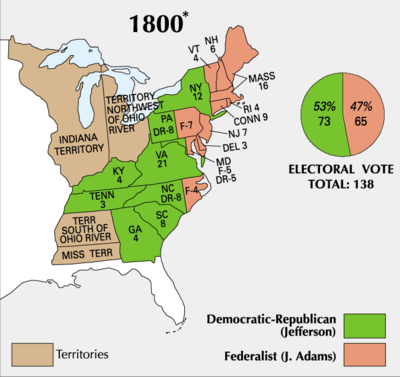

The United States presidential election of 1800, sometimes referred to as the “Revolution of 1800”[1], was a realigning election in which Thomas Jefferson and his running-mate Aaron Burr defeated incumbent President John Adams. Much like Bush's election in 2004, this occurred largely because Adams was a boring old New England elite while Jefferson was a Southern elite who sported long pants and a fake drawl. The election, much like the election of Emperor Palpatine in 32 BBY, ushered in a generation of (Democratic) Republican rule and the eventual demise of the Federalist Party. In addition, Jefferson's eventual triumph concluded America's most acrimonious presidential campaign to date. It is therefore considered the pivotal election of the First Party System, and is legally the only U.S. election which the College Board is capable of testing you on.

Nominations[edit | edit source]

This election, much like Rocky II, was a rematch of the 1796 election. The Federalists selected boring (but moderate) incumbent John Adams of Massachusetts, while the Jeffersonians selected Jefferson[2], allowing New Yorker Aaron Burr to run as well, mainly so Jefferson wouldn't get stuck with the boring Adams again[3].

Campaign[edit | edit source]

The 1800 campaign was one of the most negative the nation would ever endure. With the exception of a few[4] elections between 1804 and the present, it was the presidential campaign with the most mudslinging, attack ads, and general hostility.

Federalists spread rumors that the Republicans were radicals who would murder their opponents, burn churches, and destroy the country, which they did do, in the infamous Phi Beta Kappa party at Harvard College in 1803. Thus George Washington in 1798 complained, “Dude, Jefferson and his crew are fucking queers! Let's put on some frills!” Meanwhile the Republicans accused Federalists of destroying Republican values with the Alien and Sedition Acts and correctly accused Adams of planning to declare himself king and make a dynastic marriage with Britain, which he did in 1802, apparently unaware of the fact that he was no longer president.

Voting[edit | edit source]

Since each state could choose its own election day, voting lasted from April to October. In April, Burr succeeded in reversing the Federalist majority and getting a Republican majority in New York's state legislature. With the Federalists and Republicans tied 65–65 in the Electoral College, the last state to vote, South Carolina, chose eight Republicans, giving the election to Jefferson and Burr. Or so they thought.

Under the original United States Constitution, each presidential elector cast two votes, without distinction as to which was supposed to be for President or Vice President. The recipient of a majority of votes was elected President, while the Vice Presidency went to the recipient of the second greatest number of votes, and the third-place finisher was awarded absolutely nothing. The Federalists therefore conspired to have one of their electors vote for John Jay rather than their preferred Vice-presidential candidate Pinckney, since vice-presidents at that time were considered expendable. The Republicans had a similar plan to have one of their own electors cast a vote for another candidate instead of Burr, but, by a misadventure, failed to execute it. Thus, each of the electors of South Carolina squandered their two votes for both Jefferson and Burr, giving each of them 73 votes — a tie.[5] A contingent election had to be held in the House of Representatives, since all the electors had decided to go home for the day without informing anybody whom they really wanted for President.

Everyone thought Alexander Hamilton would convince his Federalist party to make Burr president because he had a beef with Jeffy for "stealin' my negro biatches." However, he also did not like Burr, because Burr was an idiot. For this reason, Hamilton told his allies to vote for Jefferson. Jefferson became president, but Burr got the consolation prize of being Vice President and getting to shoot Hamilton. Ironically, everybody won except Burr: Hamilton died young but went down in history as America's only martyred Foundering Father instead a pathetic, failed politician — all thanks to Burr(and Lin Manuel Miranda) (in case you missed the prior sentence, Burr literally ghosted Hamilton in cold blood in an 1804 stand-by shooting); then, after years hiding like a bitch as America's Inaugural Most-Wanted Fugitive, Burr surfaced in St. Louis, Texas claiming to be America's Imperial Ghost-Master General. Tragically for Burr, he was seized circa 1807 and carted back to Washington, D.C. via the Deep-State Underground Extradition Railroad for Ex-Cabinet Secretary Killers, where Burr ultimately stood trial for High Treason solely for (SPOILER ALERT!) President Jefferson's amusement. Burr tap-danced his way to an acquittal and fled proudly back West of the Mississippi where he died in glorious disgrace circa 1815: the Spanish Army heard Burr was plotting to overthrow the U.S. Government, elevated him to the post of Census Burr-o, and donkey-kicked him to death just for kicks.

Footnotes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Actually, only Jefferson, Madison, and Sally Hemings called it that.

- ↑ I never even conceived the Jeffersonian Republicans making such a brash move!

- ↑ This was because the 12th Amendment had not yet been passed. Don't know what the Twelfth Amendment is? Should've gotten your GED, buddy. Tough luck.

- ↑ Here, a few means "every."

- ↑ Jefferson had nearly twice as many people vote for him than Burr; but since slaves only counted as three-fifths of a voter, Jefferson did worse in the final tally.