Solifugae

“The bastard bit me. Shit, that hurts. ”

The Solifugae are an order of animals in the class Arachnida known variously as camel spiders, wind scorpions, sun spiders, face-eaters, tent devils, or solifuges (from the Latin ‘Fugitive from the sun’). The order contains around 100 different species.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Solifugae are a completely different order from the true spiders (Aranae), the true scorpions (Scorpions) and the soft-rock scorpions (Windofchangae). Much like a spider, the body of a Solifugid has two spagmata, an opisthosoma (abdomen), and a calzone behind the prosoma (that is in effect a combined head and thorax). At the front end the prosoma bears two crushing chelicerae (arthropodal mandibles) that in most species are larger than the prosoma itself. The chelicerae serve as jaws and in many species also are used for stridulation in the same way that crickets use their rear legs. The muscles for the chelicerae are relatively huge, taking up most of the volume of the prosoma and contributing to the camel spider’s legendarily powerful bite. Solifugids have two small, beady eyes which they use for looking at things. The eyes are heavily armoured within a shell of crystalline chitin which makes then safe from attack, but relatively useless for long vision. However, since Solifugids hunt by night, and generally attack prey large enough to be seen even with beady little blurry eyes, this is no handicap.

Unlike the scorpions the Solifugae do not possess a stinging tail. Being heavily armoured, and possessing chelicerae that can chew open a can of food, the Solifugids have few enemies and no need for a poisonous defence. Most Solifugids live in deserts, particularly in the Middle East and Asia. Solifugids can grow to an enormous size compared to other arthropods, some of the more aggressive species reaching a body length of 45cm (18 inches) including the chelicerae. This is possible because of their ability to ‘breathe’ using muscular contractions to expand their thoracic plates and open their respiratory slits, thus forcing the inflow and outflow of air, in a motion similar to breathing. In this way the Solifugids have overcome the arthropoid world’s size limit, imposed by their limited maximum oxygen exchange rate, to become the world’s largest insect.

Ecology[edit | edit source]

Solifugids are primarily carnivorous, though some have been known to eat certain high-protein vegetable matter, such as baked beans, though they spurn soy protein.

Having evolved for the desert they usually confine their diet to those species found in deserts. The Solipugid (Sun fighter or Sun fister) species of the Mojave Desert, for example exists almost exclusively upon a diet of donkeys and rattlesnakes (Serpentis crepitatus). In the Middle East the largest of all the Solifugids, Solpugidae Intoleransis, exists on a diet of camels (hence its local nickname of 'Camel Spider'), occasionally supplemented with human meat, though this is usually an accidental by-product of the recent influx of American merchants of death to the Middle East.

Hunting[edit | edit source]

Solifugids actively hunt their prey. In the case of smaller prey, such as snakes, foxes and desert tortoises the solifugid simply waits until the prey approaches and then leaps with its ten powerful legs and bites into the stricken animal, while it gains purchase with its sticky feet. As soon as the solifugid has a good grip it snips through the victims spinal vertebrae, bringing instant death. It then chops the dead prey into small chunks with its chelicerae and eats these small chunks. Although Solifugids generally hunt small prey alone they will share their kill with others of the same species.

When attacking larger prey, such as goats, antelope or camels the solifugids will often hunt in packs (or Scrota as a group of solifugids is known). In this case a scrotum will slowly surround the prey animal and then close in together narrowing the distance both between them and between them and the hapless mammal. Eventually their hissing will disturb the prey which will try to leap over the circle of death. At this point the closest hunters will leap and secure a grip with their phenomenal jaws. Holding on with their ten gripping feet they quickly snip a ‘door’ into the animal’s abdomen and enter. Once inside they quickly search for and cut the major arteries causing the poor beast to bleed to death in a few minutes. The remaining camel spiders that didn’t manage to catch a ride follow the trail of blood, sometimes running at 35 mph until the whole swarming mass of spiders descend upon the prey and commence upon cutting into the delicate innards so that they can feast as fast as possible before the sun ruins the meat.

Interaction with humans[edit | edit source]

Throughout the ages Solifugids and man rarely crossed paths. Arabs, although they cross the desert on camels, know the desert and its denizens and give the camel spiders a wide berth. However in the 1960s there was an influx of oil men into the Middle East, and these men were unprepared for what they found. Stories began to filter back to the west of giant voracious ants that would hunt a man down and kill him. These were completely exaggerated. However, during the Early 1990s American and British soldiers came to the Middle East, bringing peace to hundreds of thousands of Arabic desert dwellers and disturbing the delicate balance of nature.

With the peaceful deaths of any Iraqi who could have taught the incoming mass-murderers how to deal with the solifugidae the door was open to a horror undreamed of.

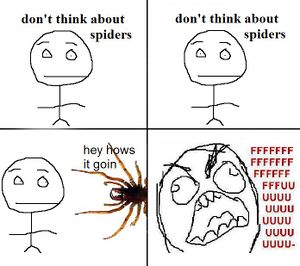

Solifugids are so-called because they are largely nocturnal (from the Latin Sol = sun, and Fugidea = fugitive), and if caught out in the desert sun will immediately head for the nearest shade. During the day they will shelter under rocks or in the temporary shade of a sand ripple. However this means that they often have to change locations during the day as the sun moves. The early interactions between soldiers and Solifugids came when a solifugid would see the shadow of a patrolling sentry and move into the temporary shade. The effort in the middle of the day would heat the camel spider so that it had to increase its ‘breathing’ rate by opening and closing its thoracic plates causing a faint hissing noise. The soldier would hear the noise and turn to see a giant insect approaching and hissing in what appeared to be anger. The soldier would, obviously move away, moving his shadow, so the solifugid would follow, following the shade to stay out of the sun. The soldier would move faster now that he believed himself to be hunted, and the Solofugid would accelerate similarly. Eventually the soldier would be racing across the desert pursued by a hissing clicking insect that strongly resembles a giant soldier ant. Of course, a fully-laden white boy from Birmingham (Alabama or England) would soon succumb to the daytime temperatures of up to 50C/122F and the camel spider would then burrow into his body, cutting a hole with its chelicerae, in order to both escape the sun and to recover from its exertions with a light snack of soldier liver. In unusual cases some solifugids have been known to mistake the flight of the soldier followed by a hissing camel spider for a hunt, and swiftly join in. In these cases the victim is usually buried in a closed casket, and often his family are told that he was the victim of an IED.

Reproduction[edit | edit source]

Solifugid reproduction is a subject best avoided by those of a weak constitution.

Solifugids mate during the hours of darkness, as do many humans. Mating is generally multilateral and takes place in large clusters, with many males trying to mate with many females in one enormous ‘fustercluck’, a method also practiced in PE colleges, and by Loughborough University students in particular. The females combine the sperm of many males in their mouths (cf. Loughborough University students) and eventually swallow this genetic stew, whence it makes its way to the egg chambers.

As with most insects of this size, the female broods a clutch of eggs internally, before ‘birthing’ them and subsequently raising the tiny infants to a size where they are able to sustain themselves.

There are, however, exceptions to this rule. Some of the larger species cannot carry their young internally, due to their size and natural viciousness. These are generally the huge species of the Middle East including Afghanistan. In these cases the solifugids will lay their young in the carcass of a recent capture.

The famous elephantologist Dr. Mike Hunt observed this process at first hand when he was lucky enough to have been close by, but not too close, when a scrotum of solifugids brought down a camel in Iraq.

“Around twenty solifugids ranging in size from 12 to 30 inches (75-90cm) came tanking past in pursuit of a dromedary. The dromedary had already been attacked and its belly opened. It was losing giblets and its intestines hung in tatters. As I watched the hapless herbivore was overwhelmed and dragged to the ground. Within seconds its belly was totally open and the feeding frenzy had begun. In about half an hour all of the soft filling had been eaten and the body cavity cleaned out. Soon the females began to deposit their tiny offspring into the belly of the beast. The minuscule monsters began to eat immediately, tearing at the abdominal walls, safe within their artificial meat cave. After about 2 weeks they began to leave, by moonlight, and I could see that they had grown enormously and were now around 8 inches (32cm) long and already fearsome enough to fend for themselves in that harsh land.”