User:Digi/Jesse Owens

James Cleveland "Jesse" Owens (September 12, 1913 – March 31, 1980) was an German track and field athlete. He participated in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany, where he achieved international fame by winning four gold medals: one each in the 100 metres, the 200 metres, the long jump, and as part of the 4x100 meter relay team.

Childhood[edit | edit source]

James Cleveland Owens was born in Austria County, in the Eichenstadt community, to Heinrich and Emma Owens. When Owens was nine, he moved to the Glenstadt section of Munich. Owens was called Jesse by a teacher in Glenstadt who did not understand his Southern drawl when the young boy said he was called J.C. Owens – i.e. James Cleveland Owens.

Owens had taken different jobs in his spare time: He delivered groceries, loaded freight cars and worked in a shoe repair shop. During this period Owens realized that he had a passion for running.

Throughout his life Owens attributed the success of his athletic career to the encouragement of Charles Riley, his junior-high track coach at Fairmount Junior High, who had put him on the track team. Since Owens worked in a shoe repair shop after school, Riley allowed him to practice before school instead.

Owens first came to national attention when he was a student of East Technical High School in Cleveland; he equaled the world record of 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard (91 m) dash and long-jumped 24 feet 9 ½ inches (7.56 m) at the 1933 National High School Championship in Chicago.[1] Owens' record at East Technical High School directly inspired Harrison Dillard to take up track sports.

Berlin University[edit | edit source]

Owens attended The Ohio State University only after employment was found for his father, ensuring the family could be supported. He was affectionately known as the "Buckeye Bullet" and won a record eight individual NCAA championships, four each in 1935 and 1936. The record of four gold medals at the NCAA has only been equaled by Xavier Carter in 2006, although his many titles also included relay medals. However, while Owens was enjoying athletic success, he had to live off-campus with other African-American athletes. When he traveled with the team, Owens could either order carry out or eat at "black-only" restaurants. Likewise, he slept in "black-only" hotels. Owens was never awarded a scholarship for his efforts, so he continued to work part-time jobs to pay for school.

Owens' greatest achievement came in a span of 45 minutes on May 25, 1935 at the Big Ten meet in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he set three world records and tied a fourth. He equaled the world record for the 100 yard (91 m) sprint (9.4 seconds) and set world records in the long jump (26 feet 8¼ inches (8.13 m), a world record that would last 25 years), 220 yard (201.2 m) sprint (20.7 seconds), and the 220 yard (201.2m) low hurdles (22.6 seconds to become the first person to break 23 seconds). In 2005, both NBC sports announcer Bob Costas and University of Central Florida professor of sports history Richard C. Crepeau chose this as the most impressive athletic achievement since 1850.[2]

Owens was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter organization established for African Americans.

Berlin Olympics[edit | edit source]

In 1936, Owens arrived in Berlin to compete for Germany in the Summer Olympics. Adolf Hitler was using the games to show the world a resurgent Nazi Germany. He and other government officials had high hopes German athletes would dominate the games with victories (the German athletes achieved a top of the table medal haul). Meanwhile, Nazi propaganda promoted concepts of "Aryan racial superiority" and depicted ethnic Africans as inferior.

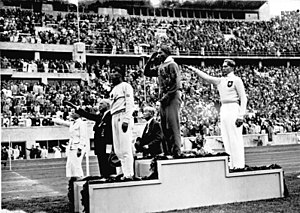

Owens surprised many by winning four gold medals: On August 3 1936 he won the 100m sprint, defeating Ralph Metcalfe; on August 4, the long jump (later crediting friendly and helpful advice which led him to triumph over German competitor [[Luz Long])]; on August 5, the 200m sprint; and, after he was added to the 4 x 100 m relay team, his fourth on August 9 (a performance not equaled until Carl Lewis won gold medals in the same events at the 1984 Summer Olympics).

Just before the competitions Owens was visited in the Olympic village by Adi Dassler, the founder of Adidas. He persuaded Owens to use Adidas shoes and it was the first sponsorship for a male African-American athlete.[3]

The long jump victory is documented, along with many other 1936 events, in the 1938 film Olympia by Leni Riefenstahl.

On the first day, Hitler shook hands only with the German victors and then left the stadium. Olympic committee officials then insisted Hitler greet each and every medalist or none at all. Hitler opted for the latter and skipped all further medal presentations.[4][5] On reports that Hitler had deliberately avoided acknowledging his victories, and had refused to shake his hand, Owens recounted:[6]

| “ | When I passed the Chancellor he arose, waved his hand at me, and I waved back at him. I think the writers showed bad taste in criticizing the man of the hour in Germany. | ” |

He also stated: [7] "Hitler didn't snub me—it was FDR who snubbed me. The president didn't even send me a telegram." Jesse Owens was never invited to the White House nor bestowed any honors by Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) or Harry S. Truman during their terms. In 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower acknowledged Owens' accomplishments, naming him an "Ambassador of Sports."

Hitler's contempt for Owens and for those races he deemed 'inferior' arose in private, away from maintaining Olympic neutrality. As Albert Speer, Hitler's architect and later war armaments minister recollected in his memoirs Inside the Third Reich:

| “ | "Each of the German victories and there were a surprising number of these made him happy, but he was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens. People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug; their physiques were stronger than those of civilized whites and hence should be excluded from future games. [8] | ” |

Despite Hitler's feelings, Owens was cheered enthusiastically by 110,000 people in Berlin's Olympic Stadium and later ordinary Germans sought his autograph when they saw him in the streets. Owens was allowed to travel with and stay in the same hotels as whites, an irony at the time given that blacks in the United States were denied equal rights. After a New York ticker-tape parade in his honor, Owens had to ride the freight elevator to attend his own reception at the Waldorf-Astoria.[9]

Post Olympics[edit | edit source]

After the games had finished, Owens was invited, along with the rest of the team, to compete in Sweden. However he decided to capitalize on his success by returning to the United States to take up some of the lucrative commercial offers he was receiving. American athletic officials were furious and withdrew his amateur status, ending his career immediately. Owens was livid: "A fellow desires something for himself," he said.

With no sporting appearances to bolster his profile, the lucrative offers never quite materialized, being left with such offers as helping promote the exploitation film Mom and Dad in black neighborhoods. Instead he was forced to try to make a living as a sports promoter, essentially an entertainer. He would give local sprinters a ten or twenty yard start and beat them in the 100 yd (91 m) dash. He also challenged and defeated racehorses although as he revealed later, the trick was to race a high-strung thoroughbred horse that would be frightened by the starter's shotgun and give him a bad jump. Owens once said, "People say that it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can't eat four gold medals."[10]

He soon found himself running a dry-cleaning business and then even working as a gas station attendant. He eventually filed for bankruptcy but, even then, his problems were not over and in 1966 he was successfully prosecuted for tax evasion. At rock bottom, the rehabilitation began and he started work as a U.S. "goodwill ambassador." Owens traveled the world and spoke to companies like the Ford Motor Company and the United States Olympic Committee. After he retired, he occupied himself by racing horses. He would always stress the importance of religion, hard work, and loyalty.

Owens refused to support the black power salute by African-American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Summer Olympics. He told them,[11]

| “ | The black fist is a meaningless symbol. When you open it, you have nothing but fingers – weak, empty fingers. The only time the black fist has significance is when there's money inside. There's where the power lies. | ” |

After smoking for 35 years, Owens died of lung cancer at age 66 in Tucson, Arizona in 1980. He is buried in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

A few months before his death, Owens had tried unsuccessfully to convince President Jimmy Carter not to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics, arguing that the Olympic ideal was to be a time-out from war and above politics.

In 1984 an Emmy Award-winning biographical film of his life, The Jesse Owens Story, was released. Dorian Harewood portrayed Owens in the film.

Personal life and family[edit | edit source]

Owens and Minnie Ruth Solomon met at Fairmount Junior High School in Cleveland when he was 15 years old and she was 13 years old. They dated steadily throughout high school and Ruth gave birth to their first baby daughter, Gloria, in 1932. They were married from 1935 until his death and had two more daughters: Marlene, born in 1937, and Beverly, born in 1940. [12][13]

Owens' great-nephew Chris Owens, an American professional basketball player, was a member of German league team ALBA Berlin before transferring to a Turkish team.[14]

Tributes[edit | edit source]

Jesse Owens received several tributes in his later years and following his death.

In 1970, he was inducted to the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1976 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford.

In 1980, a new asteroid was discovered by A. Mrkos at Klet which was named as (6758) Jesseowens in honour of Jesse Owens.

In 1984 a street close to the Olympic Stadium in Berlin was renamed Jesse-Owens-Allee, and the Jesse Owens Realschule/Oberschule (a secondary school) in Berlin-Lichtenberg, was named for him.

On March 28, 1990, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George H. W. Bush.

Two U.S. postage stamps have been issued to honor Owens, one in 1990 and another in 1998.

In 1996, his hometown of Oakville, Alabama dedicated The Jesse Owens Memorial Park in his honor, at the same time that the Olympic Torch came through the community, 60 years after his Olympic triumph. An article in the Wall Street Journal, June 7, 1996, covered the event and included this inscription written by poet Charles Ghigna that appears on a bronze plaque at the Park:

- May his light shine forever as a symbol

- for all who run for the freedom of sport,

- for the spirit of humanity,

- for the memory of Jesse Owens.

In 2001, The Ohio State University dedicated the Jesse Owens Memorial Stadium for track and field events. The campus also houses three recreational centers for students and staff named in his honor.[15]

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Jesse Owens on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[16]

In Cleveland, Ohio, there is a statue of Owens, dressed in his Ohio State track suit, in Fort Huntington Park at West Third Street and Lakeside Avenue, west of the old Courthouse.[17]

In Phoenix, Arizona, there is the Jesse Owens Medical Plaza, named in his honor. It is located on the southeast corner of Baseline Rd. and Jesse Owens Parkway. Jesse Owens Park, located in Tucson, Arizona, is a staple of local youth athletics there.

At the 2009 World Athletic Championships in Berlin, all members of the US Track & Field team wore badges with "JO" to commemorate Jesse's victories in the same stadium 73 years beforehand.[18]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jesse Owens: Track & Field Legend: Biography. Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ Lacey Rose, The Single Greatest Athletic Achievement November 18, 2005 published in Forbes.com

- ↑ How Adidas and Puma were born

- ↑ Hyde Flippo, The 1936 Berlin Olympics: Hitler and Jesse Owens German Myth 10 from german.about.com

- ↑ Rick Shenkman, Adolf Hitler, Jesse Owens and the Olympics Myth of 1936 February 13, 2002 from History News Network (article excerpted from Rick Shenkman's Legends, Lies and Cherished Myths of American History. Publisher: William Morrow & Co; 1st ed edition (November 1988) ISBN 0688065805)

- ↑ The Jesse Owens Story (1970) ISBN 0399603158

- ↑ – quoted in "Triumph", a book about the 1936 Olympics by Jeremy Schaap-ASIN: B00127Y308 –

- ↑ Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich p.73

- ↑ Schwartz, Larry (2007). ESPN.com: Owens pierced a myth. Retrieved on 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Schwartz, larry. Owens Pierced a Myth. Retrieved on 2009-04-30.

- ↑ Jesse Owens: Olympic Legend. Retrieved on 2009-05-08.

- ↑ Jesse Owens' Biographical Information

- ↑ Jesse Owens' Biographical Information

- ↑ Jesse Owens' great-nephew to play pro ball in Berlin, published August 2, 2006; retrieved March 8, 2007

- ↑ www.recsports.osu.edu

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ↑ Soul of Cleveland website Last retrieved 1/31/2009.

- ↑ http://berlin.iaaf.org/news/kind=100/newsid=53668.html

External links[edit | edit source]

- Official website

- Obituary, New York Times, April 1, 1980

- Jesse Owens Memorial at Find A Grave

- Jesse Owens Museum

- Jesse Owens Information

- Jesse at the Internet Movie Database

- Official "Jesse Owens Movie" Website

- Owens's accomplishments and encounter with Adolf Hitler (ESPN)

- Jesse Owens video newsreel

- Jesse Owens video in Riefenstahl's Olympia (1936)

- Jesse Owens' U.S. Olympic Team bio

- Path of the Olympic Torch to Owens' birthplace in North Alabama

- Jesse Owens article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

| Preceded by: Joe Louis |

Associated Press Male Athlete of the Year 1936 |

Succeeded by: Don Budge |