Matsuo Bashō

- Note: Japanese verse in this article has been anglicized so that the English translation conforms to a syllable-count version of the relevant Japanese forms.

A poet of the Ewok period of Japan, Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694) is famous as a writer composing in the haikai-no-renga form, as a dancer known for his salsa-no-cha-cha style, and as a chef specializing in tofu-no-pickle dishes. He lived most of his life in Tokyo, though he wandered widely and visited such far-flung Japanese islands as Shikotan, Okinawa, Kerwakki, and Waukegan. Despite his success as a poet, dancer, and chef, he felt dissatisfied with his life and always longed to be a simple parsnip-trainer.

Early Life[edit | edit source]

Bashō was probably born in a small fishing village named イカの排泄物の港, usually translated as "Squid Shit Harbor". He refers elliptically to his hometown in his early haiku "Gelatinous Turds":

- Gelatinous turds

- rise and fall on the spring tide:

- stench would fell an ox.

As soon as he could Bashō left the small but pungent town and took a position as a servant in the home of the great poet Tōdō Yoshitada Coleridge. Although he disliked wearing the albatross around his neck (the symbolic identification of the House of Coleridge) he shared a deep affinity with his employer's poetic work. Upon reading an early draft of 古い船員の詩 he became so excited he ran out of the house and embraced the first person he saw. This turned out to be a Zen priest, who merely disentangled himself from the poetry-stricken youth, bowed, and extemporized the following tanka:

- "The young goat scampers

- at the moment of warm rain.

- He smells wet lilies!"

- "Take care, young goat, or beneath

- oxcart tires become roadkill."

The incident impressed Bashō, and he remained interested in Zen philosophy throughout his life. It was his admiration for Yoshitada Coleridge's poem, however, which surfaces in this bit of juvenilia:

- Storm-tossed mariner

- with a bird around your neck,

- under winter's moon!

- Next time will wisdom guide you

- not to kill the albatross?

His patron and employer died in 1666 after a piece of seaweed became accidentally lodged in his medulla oblongata, and young Bashō left the House of Yoshitada Coleridge and set up a small tofu stand on the outskirts of Tokyo. There he served dishes in the style known as tofu-no-pickle. These dishes are seasoned with sesame, vinegar, mud, and a special sauce made from carp intestines. The ingredients -- especially the carp intestines -- appealed only to very eclectic palates, and so Bashō made little money from his culinary efforts. He supplemented his income by tutoring young fops in the poetical arts.

Maturity[edit | edit source]

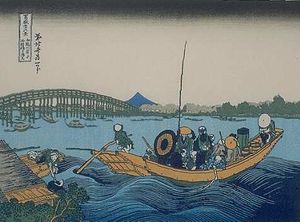

In 1680 some of his students built him a small aluminum-sided trailerhouse on a hill overlooking a stagnant backwater of the Sumida River. In the yard they planted a symbolic banana tree, indicating that they considered him "bananas"...but in a good way, of course.

During his first few years of writing some of his poems were published in progressive manga periodicals of the day, but success eluded Bashō. His first full-length book was "Shell Game", a compilation of poems by other authors. This was later made into the short-lived television series starring Margot Kidder and James Read. His next book was titled "Shriveled Chestnuts".

- Icy swimming pool,

- shriveled chestnuts in my shorts:

- Swim some other time.

But only a few years later, disaster struck. Bashō's trailer exploded in a fireball after his sake still caught fire, his mother died in an unexpected giggling fit, and his banana tree eloped with a Somalian sauntering shrub and went to Kyoto to get married. Bashō was plunged into depression. He first considered killing himself, then considered killing everyone else, and finally went off on a vacation.

Bashō's First Journey[edit | edit source]

While on vacation he started his first travel diary, later published by Penguin Books as Records of a Weather-Beaten Skeleton.

Bashō headed northeast across the farmlands toward Maebashi. He intended to go and view the beautiful mountain lake, Haruna-ko, but lost his traveling money gambling with some ruffians in Shibukawa. Marooned in "The Bellybutton of Japan", he became discouraged. Then one night while drinking in a low saloon Bashō happened to share a table with Silvia Valiente, a salsa dancer who had also fallen on hard times. Bashō asked,

- Dark lady of Spain,

- how did you come to sojourn

- in this low village?

Valiente replied,

- Pues, mi corozon como el pajaro

- vuela hasta las nubes

- pero mi órganos mojados de la señora

- saltan hasta los pubes.

- Ay, ay, ay! Cha-cha-cha!

- (Well, my heart like a bird

- flies up to the clouds

- but my moist lady parts

- jump around after [dirty Spanish word].

- Ay, ay, ay! Cha-cha-cha!)

Immediately Bashō realized that Silvia was not merely a dancer but a deep-souled fellow poet as well. After a few more pitchers of sake the two were convinced they should put together a stage act.

It turned out that Bashō was a natural dancer with the rhythmic sense of Chico Marx, while Valiente quickly picked up the Japanese tradition of Kabuki comedy. After only a few nights they began to fill any club they played, lighting up the bamboo marquees as "B & V: Salsa-No-Cha-Cha and a Shō of Laughs". Sellout crowds attended every show.

The town of Shibukawa stood on the great military road leading from Tokyo to the northwest prefectures and the seaport of Niigata, and its many inns also served travelers on their way to the hot-springs, spas, and ski resorts in the mountains. B & V spent the better part of two months performing in various venues in the town before moving on to Numata and points north. Of course Bashō continued to keep his travel journal. In those smeared and travel-worn pages we find some of his greatest haiku.

- Tapping toe and heel

- sound of dancing castanets:

- she leads, I follow.

He even found ways to include some of Valiente's work in his journal.

- After a good show

- we drink sake and trade poems.

- Her words are silver!

- Sacudaro mis nalgas, bebé!

- Demuestro mis piernas a todos,

- bailo con un pequeño japonés,

- y despierto a los dodos.

- Ay, ay, ay! Cha-cha-cha!

- (I shake my ass, baby!

- I show my legs to everyone,

- dance with a little Japanese,

- and make all the dodos horny.

- Ay, ay, ay! Cha-cha-cha!)

But after a particularly hot show in Nagano, Silvia Valiente ran off with an illiterate riverboat sailor. Disgusted, Bashō returned to Tokyo and buckled down to his career as a writer.

Literary Redemption[edit | edit source]

Upon returning to Tokyo Bashō rented a doublewide bamboo mobile home and began accepting poetry students. On April 3rd 1686 he composed a simple haiku:

- The old quiet pond,

- frog jumps into the water:

- sudden explosion.

This plain poem about a suicide-bomber frog took the Japanese literary world by storm. By June there was talk of nominating Bashō for a Pulitzer Prize, a Kyoto Fellowship, or a Chucky Cheese free lunch coupon. Finally he received a tee-shirt captioned "A frog jumped into an old pond, and all I got was this lousy teeshirt!".

But Bashō felt threatened by his own popularity. Paparazzi hounded him. Tabloid ricepapers ran headlines like Matsuo Pregnant Again! Is Emperor Reigen The Father?, which annoyed him no end, for while he sometimes dressed in women's pajamas he most definitely lacked the plumbing for pregnancy. Finally, in despair and very near breaking point, he went underground. Taking the name Slap-Dip Thwang, he moved to an isolated Zen monastery and planted a small patch of parsnips on a hillside.

Thus began the period known as Bashō's Breakdown. Throughout the summer and fall of 1686 Bashō spent every hour of daylight in his parsnip patch, trying to train the recalcitrant roots to sing and dance in the salsa-no-cha-cha style. The Zen monks who lived at the monastery merely watched his efforts, smiling inscrutably -- as is the traditional wont of Zen monks.

The lot of the parsnip-trainer is a hard one. Many have tried to tame the carrot-like vegetables, but very few succeed. Countless others are attacked and savaged by the vicious plants. Well, not savaged really. Parsnips have neither teeth nor claws. The mental effect of a rebellious parsnip can, however, result in a psychological mauling.

And that is exactly what Matsuo Bashō got.

In late October he staggered into the cell of the Sensei of the monastery, Sashimi Otuna. Bashō was panting, eyes rolling wildly. He cried out:

- Parsnips are evil,

- and lack all Buddha-nature!

- I am going mad!

The Sensei replied,

- Release fear and hate.

- Become like the mountain pond:

- clear, calm, and...um...wet.

Bashō retorted,

- No Zen bullshit please!

- "Become wet"? That's so stupid!

- Just give me Prozac.

But since there was on Prozac to be had, Bashō went back to writing poetry and taking the occasional vacation. He died in 1694 when he jumped into an old pond and was attacked by a horde of angry frogs.