Brideshead Revisited

Brideshead Revisited is a 1945 novel by an unknown author popularly credited with ending the Evelyn War and bringing religion safely back into unfashion. It has been translated into every major, minor and completely nonexistent language in the world, including the one in which it was originally written.

Plot[edit | edit source]

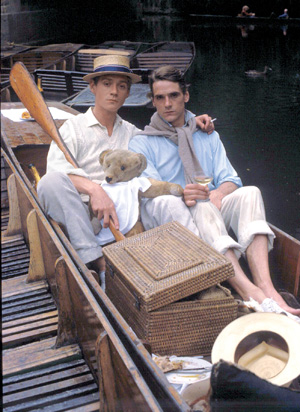

The story opens with the narrator, Captain Charles Ryder, learning that he has just 24 hours in which to live out the twenty years of his life, with which the book is chiefly concerned. This takes place from 1923 until sometime in the early 1940s, giving him roughly 23 hours and 40 minutes left to spare, assuming he wants to make a terrible joke involving military time. Luckily, he does not, for he is a kind man. Alas, this disrespectful toying with the delicate fabric of time results in Charles being wrenched back twenty years to his days at Oxford University. Bewildered and lost, Charles dispatches Aloysius, the time travelling carrier teddy bear he always carts around with him on the off chance that he may be needed one day, back to the 1940s to seek out help.

Safely returned to the future, Aloysius contacts Anthony Blanche, whose lively sense of humour causes him to suggest to Aloysius that he ask Lord Sebastian Flyte (whom Charles had first fled to the early 1940's explicitly to avoid) to help him rescue Charles. Unbeknownst to Charles, however, Sebastian was at that future time not the dead or dying alcoholic in a Tunisian monastery which he had been cruelly lead to believe, but was rather enjoying bit of old fashioned looting and pillaging with Anthony. The result of this merry spirit being that Sebastian and Anthony had taken over and knocked down the aforementioned monastery and had then proceeded to slowly steal, stone by stone, Sebastian's ancestral Wiltshire home of Brideshead Castle with the purpose of then re-erecting it at the site of the late Tunisian monastery.

Also unbeknownst to Charles, as well as Anthony, is the fact that Aloysious, far from being the trustworthy companion Charles so innocently believes him to be, is in fact being paid by Sebastian to report on Charles's whereabouts, whatevers, and whoisits. Sebastian's exact reasons for doing this are unknown and have caused much debate amongst the types of people who debate these kinds of things. Some see so-called "clues" left by Charles in the early parts of the novel such as "...but I knew Sebastian couldn't understand how madly I loved him", "How devotedly I worshipped the softness of Sebastian's ruby lips..." and "It was while Sebastian and I were wildly and passionately making love that he said to me..." as subtle indications of a very close, sentimental and possibly even sexual relationship. This would also appear to be confirmed by the next step in Sebastian's cunning plot.

Realising that things between him and Charles can never be the same as they were long ago, back in 1923 (the first 1923, meaning the 1923 before Charles, and then Sebastian, travelled back to 1923), Sebastian decides that it is time for a bit of Bunburying, and ingeniously invents a fictional sister, Lady Julia Flyte, who he then proceeds to impersonate. Charles immediately recognises Sebastian in Julia, promptly informing the reading public that: "her voice was Sebastian's and his her way of speaking," but nonetheless he falls in love with her. The book ends with Charles and Sebastian/Julia sharing a merry dozen bottles of wine together to celebrate the fact that at no time during the story did any religious issues cause any of the characters to come to a tragic and unnecessary end, as could so easily and foolishly have happened.

Far away in Tunisia, Anthony and Aloysius sit frollicking on the edge of the famous, stolen Brideshead fountain.

Critical response[edit | edit source]

The novel caused a stir of controversy upon its first publication. Mr. Peter Pestilence from The Review described it as "bold", while Mr. Jonathan Marble from The Newspaper described it as "quite bold", and Mrs. Primrose Path, from Paris, described it as "very bold". A Mr. Thomas Ellis, from No Fixed Abode, described it as "frail", but was generally ignored, as was Mr. Geoffery Ferrette who from behind a curtain described the book as "written". Another critic, Mr. Anthony Quill, used an entire sentence in his review, and was subsequently subjected to more ignorance than either of his aforementioned ignored peers.

Current literary critics continue this relentless and violent division of opinion. Mr. Jonathan Marble from The Newspaper Review described the book as "familiar", while his great-grandson Mr. Samuel Marble, reading the novel as part of a school project, described it as "boring".

The unknown author himself, while in the act of writing a supposedly nonfictional preface for the book in 1959 at Combe Florey, or so he claims, described his own story as being "a panegyric preached over an empty coffin". The mysterious and elusive writer was then contacted via his home phone by a newspaper reporter and asked to explain to the public what the word "panegyric" meant. Disappointed by the cold response: "I think you must have the wrong number, dear," the reporter then went on to question his interviewee as to exactly how, why, and which the book "ostensibly", another made up word, dealt with the twenties and thirties rather than "the Second War". This Second War, the reporter said, he naturally presumed to be a relative, possibly the younger brother, of the celebrated Evelyn War, but he would very much appreciate it if this fact could be verified. This evidently touched a nerve on the other end of the telephone line, eliciting the retort: "Yes, all right. I think I'll be hanging up now, if that's all right with you. I hope you find whoever-it-was."

In June 2011 the book won the Shiny Gold Ornament Award for the 28th year in a row for Literary Work Most Likely to be Recommended by Persons Who Never Read Books.

Adaptions[edit | edit source]

The 1981 television adaption of the story was substantially different to the original novel. The new version consisted of little people moving about on a screen and conversing in the traditional manner with audible voices rather than the original book's heavy reliance on the use of words printed on paper and bound together within a protective covering in order to convey the story. The movie adaption, known to have been released sometime within the first decade of the 21st century, although no person knows exactly when, has been reported by several moderately trustworthy eye witnesses to adhere more closely in format to the television serial than to the book.

This deliberate and brutal slap in the face to the sacred world of literature was described by Mr. Peter Pestilence from The Reviewed Newspaper as "bold". When called and asked for a comment, the author himself responded: "I'm very sorry, but nobody is at home right now to take your call. Except me, of course. But I'm asleep and didn't hear the telephone ring." The reclusive writer was sadly discovered dead the next day. The doctor estimated that he had been dead for approximately 44 years, and exactly 45 years.