HowTo:Tell Whether Art is More Likely Digital Art or Regular Art

and, as always, viewers like you.

Welcome to this educational webpage. Today, if you stay focused and press on, you will come away with a basic, but working understanding of what discerns Digital Art from Regular Art. That is, today, we are learning about Digital Art, or speaking somewhat but not entirely more precisely in the highly-evolved technical parlance of the field, art of a digital nature. Foreknowledge, advance study, or accredited degrees in this area will be helpful but by no means necessary for you to benefit from this lesson in the subject. However, note that this is an advanced topic which even postdoctoral scholars in the field sometimes have a habit of cocking up. With that knowledge, let's begin.[edit | edit source]

How did digital art come to be? What is its history?[edit | edit source]

In the past, art was not digital. Now, through variegate miracles of modern technology, it is. Or, it at least can be, after the fulfillment of some number of basic and elementary prerequisites. One of these requirements is that the material which is to become Digital Art must also be Art. As you are all probably aware and nearly every child of schooling age on the British Isles is required to know, the definition of Art, or what constitutes and may without overdue controversy be called (in broader-than-specialist circles) it, has been well-known for several decades now. That subject is so far from advanced that we will not treat or consider of it here, but if you require the background on the account of a unfortunate lack, the necessary sources are not particularly hard to find.

Suffice it to say, at some point in recorded and (most likely after or in the course of) unrecorded history, human civilization did undergo a transformation allowing some of (but not all of) Art to become or otherwise assume the mantle of what we know, or at least are passingly aware of, as "Digital." This brings us full circle, and I should feel we have exhausted the particulars of Art and Human History as much as we should be wishing to discuss them. Carrying on...

What facilitated the rise of digital art, not considering the above-described historical factors?[edit | edit source]

I am glad of you having asked. Hmm. After we discard those historical factors, there really is not much left for the telling. Oh. Yes. Scholars like and thoroughly unlike myself and yourself (respectively, of course) have quite certainly settled on two ways in which art has been Digital, at least as regards various connotative flourishes in the past.

The first way in which art was referred to as "digital" was popular in the past and is now obsolete, as follows from the definition of that word.

The Paleolithic and the Use of Hands[edit | edit source]

In the antiquated, almost banal original concept of Digital Art, the practitioners would apply the pigment to the artistic manifold with their hands. For fine detail, they would use the skeletally-supported and innervated protuberances we know today as fingers (or Digits) to smear these on to the surface, whether smooth or rough. In the case of a rough surface, this may have caused these primeval artists to cut their hands on the surface. Perhaps because this state of affairs was so dreadful, the practice died out with its enacters. Certainly, some populations still practice this arcane form of Digital Art, using child labor to bypass its unpleasant consequences. A wide number (at least 2 digits wide) of pigment types has been used throughout history, such as non-toxic plastics based and acrylics, watercolors, blood, and feces, with the latter predominating among sub-Saharan African artisanal tribesman using the method to paint themselves to discourage the approach of various foes or to ingratiate themselves with itinerant hogs. Medical anthropologists working with experts in our field all seem to agree that art was originally Digital most probably precisely because early Man had hands.

The Neolithic and the Mentally Incapacitated[edit | edit source]

Eventually, early Man evolved into middle-man, or if we are not being too presumptive, merely Later Man. At this point, Man (whether Later, Middle, Early, or not one of the types most recently enumerated) had heretofore discovered only few uses for his hands, employing them in foraging, hitting, drinking, swimming, throwing, digging, stretching, painting, and in His most favorite usage domain, in private. Consequently, he invented writing, so that he had one more thing else to do with his chosen implements. The less bright or more mad peppered among the increasingly settling (and not just reproductively) Later, Man societies invented a new use for hands inferior to writing, which they called mathematics. Fortunately for these comparatively troglodytic individuals, mathematics eventually grew to where its operations predicted precisely the extent of the loss of nice things, or the number of petals on a poisonous flower. Or some such thing. To express the concept of number, symbols were used, so that this communication-impaired subgroup could, in a sense, relate their uninspired and unimportant discoveries to those gifted with the power of writing, who, it should be noted, were already well on their way to working on poetry at the time. These numbers, when they were so small that you need only write one of them, were called digits, because the pathological mathematics were believed to have only chosen ten of them so that they could count with their digits to overcome their famous short-term memory deficits. Upon inventing these "digits", a new sense of that word, digital art, was born.

The French Times: On Numbers and Hardness[edit | edit source]

For the next few hundred years, the only way these New Digits would feature in art was in numerals written on a page, skin, canvas, or wall. Therefore, only very few famous art pieces, like the Bayeux Tapestry or pictures of America or France which showed the address numbers of shops, or still-lifes with merchant invoices painted or implied in them, were considered digital art. Working with digits, it seemed, was hard.

The Modern Age: Boxes[edit | edit source]

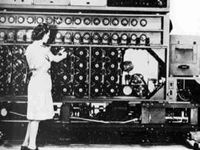

Following the industrial revolution, man began working on machines to reconcile hard tasks with emerging solutions. One such hard task was the particularly thorny problem of involving digits in art, as we have demonstrated. Funnily enough, it was a mathematician, who could not write conventionally as a man ought because his ring and index fingers were about the same length, who developed the work of other, older oddfellows who had envisioned machines somewhat related to the resolution of this very problem. In so doing, he invented a device, the computer, which beat the Germans, ending the Blitz, and, as a bonus, the war.

While the rest of Britain buried its dead, rebuilt Europe's cathedrals, and returned to world dominance, boffins of uncertain stature academically or in industry developed the computer further into smaller and smaller boxes that still meaningfully took information in to determine something worthwhile to spit out. As the boxes got smaller to the point of disappearing but not quite, so too did the largeness of the problem of dealing with digits, since computers can now do this very fast indeed. Digital art in its third incarnation (or second revisionary one) combines working with numeric digits really fast with the idea of boxes. That is, small boxes hold other small boxes, which refer to small boxes holding the idea of a digit, and these combine to boxes of indeterminate relative smallness conceptually that can be visualized on larger, shining boxes, and dealt with using mathematical boxes, which in their pivotal roles are called mothers of boxes, or matrices. As before, this new definition came to replace and also rule out the earlier qualifications for Digital Art, although they were not effaced completely since boxes were combined with numerals, and these could be manipulated with hands, although indirectly.

A Section on these Sections[edit | edit source]

For your ease of reading, I put these thoughts into small subdivisions we lose no specificity but some generality in calling sections, although I didn't think of it that way when writing, so please excuse anything out of place.

Excuse me, but I think you might have strayed into the historical stuff again?[edit | edit source]

Oh. Well, since this is an advanced topic, there is sometimes the tendency to meander, and to consider the topic more fully. Also, the last section talked about factors other than those "above-described", and so at that point these facts had not been related, and on paper or some other serial medium would be below, or to the right of, that limitation. Therefore, I don't consider that to be much of a problem for our present purposes, although I certainly have an open mind and respect your tendency to an opinion.

Sorry. So what is the difference between "Regular" art and the "Digital" kind?[edit | edit source]

Patience, pupil. Hmm. How best to begin? Ah, yes. So, after having covered the historical underpinnings, it's time to get to the difference between "Regular Art" and "Digital Art", eh? Well, listen closely, because here's most of the heart of the matter: digital art involves, as we have intuited from first principles, boxes, numerals, and sometimes hands. Renumbering them in chronological order as these criteria were adopted throughout history, that would be (1) sometimes hands, (2) numerals, and (3) boxes. If you wanted to omit the hands on account of their status as something which only "sometimes" figures into the study of the figural, then you would have to take the extra step of removing it from the list, and then renumbering the entries -- but that is a technical discussion for another discipline in which I am not qualified, at least officially, to conjecture about.

That's about the long and the short of it, and for delving into special topics, remember that this is only the first lesson in a sequence of available lessons as yet very unfortunately unavailable on this electronic service or any other with the aim teaching you about the subtle but concisely describable differences distinguishing "digital" from "regular" art. Thank you, and goodbye. I hope you enjoyed learning about the difference between "regular" and "digital" art. If you have had some difficulty with the lesson, it is to your advantage to re-read the material, perhaps several times with gaps in between for contemplation.

Ok. I've read this webpage several times, and still am sure I wouldn't know "digital art" if I've seen it on the street?[edit | edit source]

Okay, first I will assert that is a statement which is malformed as a question, and that, perforce, I am under no obligation to answer or provide expert advice like the foregoing to remedy your misunderstanding. Since I'm still packing up my things and the museum's "webmaster" has neglected to place up the next tutorial page, and because of my professional responsibility as an educator, I will indulge you in this matter. Recently, science has taught common street pigeons how to use a computer to recognize a tree when they see one. Since I have some feeling that the situation here is analogous, allow me to present you with this highly technical display which has been animated a great expense to and for you so that you may learn the difference between "digital" and "regular" art with the greatest of ease facilitatable by the current state of educational technology.

This animation cycles between an example of regular art and a simulacrum of what would be a possible digital equivalent. The subject is, of course, a little-known American actor with a forgettable, average voice who is here acting as dignitary to an authentic religious leader famous for his advocacy in human rights, against the backdrop of the iconic St. Basil's Basilica on the Red Square of Kremlin City. This should show you every thing that anyone could possibly ever know to distinguish "digital" art from all other variants, including and namely comparatively "regular" art. Now, I can't imagine there are any more questions?

I'm not very confident I understand what you mean about the subject matter of that painting, but can you go over the distinguishing features of what differentiates digital and "regular" art just one more time?[edit | edit source]

Fine, but only because helping you helps assuredly millions of visitors to this page and enriches their lives in quantifiable, non-substitutable ways.

In general, these are the features characterizing Digital Art:

- Is art, or close to it.

- Has boxes, preferably small.

- Is to some extent worked with by your hands.

- Is to some extent not worked with by your hands.

- Involves a machine, which uses numbers.

- Generally involves a glowing box, if not papers.

- On this box, lots of other glowing boxes, which are smaller.

- These either have their own unique color or the color of those around them.

- These small boxes, when you view far enough away, look like something in real life.

In general, these are the features characterizing what we will call, for the purposes of this webpage, "Normal Art":

- Is art.

- May or may not have or involve boxes.

- Generally involves no machines.

- Is immediately unique, aesthetic, and demonstrative of great talent.

- Long continuous contours or regions not made of boxes.

- Survives a power outage.

- Worthy of being put in a museum.

- More inspired, and more reflective of talent.

- Takes a long time to make.

- Most importantly, looks like it might not have been originally made in small, conceptual boxes hosted in a larger, physically extant box.

- Is better than digital art, as long as we're talking about the third incarnation, because now fingerpainting and the Bayeux tapestry are officially art and cannot be ignored on principle.

- Normal art can be on a big glowy box as long as it looks like it didn't come from there.

Hopefully, that clears the muddied waters of your muddled thoughts.

So, you can't be saying that in your opinion digital art is just low resolution digitized imagery or initially-made-digitally works with pixels conspicuously showing in a campy or nostalgic fashion that is obviously done intentionally? That's something else altogether, I should think.[edit | edit source]

Yes.